So what happened is, I mentioned The Trap Door in the last article, which made me remember “oh yeah, there’s another Trap Door game I haven’t written about! Forget about what I was going to cover this time, I’m going to write about that other Trap Door game.” This, as it happens, was example of me shooting myself in the foot. Actually, “punching myself in the balls” might be a more apt metaphor. It’s the ZX Spectrum version of Piranha Game’s 1987 you’re-a-fool-if-you-dare-em-up Through the Trap Door!

I wrote about the first home computer Trap Door game a while back, and any questions I may have had about whether this was a direct sequel are answered by the title screen. It’s exactly the same as the title screen from the first game, except the artist has just about managed to squeeze the word “Through” in there. That doesn’t exactly bode well for innovation and imagination, does it?

Through the Trap Door is, of course, based on the classic British kid’s claymation show The Trap Door. It’s a show I loved then and still love now, and it’s certainly held up a lot better than other childhood favourites like He-Man or Transformers, possibly because it’s not an obvious toy commercial but also because it’s just so darned loveable. A quick recap: Trap Door is the story of Berk, an amiable blue lump of a monster who lives in a spooky castle and performs two main duties: acting as servant, chef and general dogsbody to The Thing Upstairs (the castle’s unseen but very demanding master) and guarding the titular trap door. The trap door covers a pit that leads to a vast underground space filled with all manner of horrible, disgusting monsters. Berk is… not great at guarding the trap door, and most episodes revolve around something escaping from the pit – often because Berk left the trap door open after throwing rubbish down the hole – and Berk and his friends having to beat it back to the stygian plasticine underworld that spawned it.

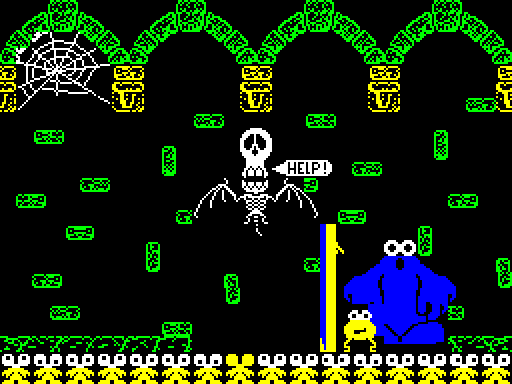

Here’s Berk and his friends now. The small lump next to him is the scuttling, beeping spider-mouse-thing Drutt, who is grey in the show but is coloured yellow in this game, thanks either to the Spectrum’s colour limitations or in the interests of keeping him visible against the background. In the middle of the screen is Boni, the miserable, melancholy talking skull who just wants to live peacefully in his little cave and not get involved with the various hijinks, and who is therefore a character I can really identify with.

Sadly, Boni’s hopes for peace and quiet are soon shattered – as they so often are when you live in a monster-filled castle – when a headless skeletal bird flies out of the trap door and affixes itself to Boni. That’s a real stroke of luck for the headless skeletal bird, but it’s not so good for Boni as his new avian body flies itself back into the trap door, leaving Berk and Drutt with a mission to rescue their calcium-rich chum.

Ever the practical sort, Berk wastes no time in jumping straight down the trap door with Drutt in hand. Berk smashes into the floor in a pleasingly cartoonish manner, while Drutt looks on, completely unscathed. Unfortunately the Spectrum’s sound hardware can’t replicate Drutt’s high-pitched giggle, but I guarantee he’s laughing at Berk right now.

So, now we’re in the trap door, what are we actually supposed to be doing?

Well, there’s a locked door over here, so finding a key seems like a reasonable first step. Once found, I can pick the key up and bring it over to the locked door, because that’s the kind of game Through the Trap Door is: a sort of graphic adventure without the parser, plus some platforming. It’s exactly the same system as the first game in the series, with Berk able to waddle around, pick up one item at a time, carry it around, drop it, use it or eat it. The big difference is that rather than fulfilling tasks for The Thing Upstairs, you’re trying to rescue Boni, which means there’s even less guidance here than in the prequel. In fact, almost none of the items give you any clue as to their purpose or function. For instance, there’s a red sweet floating in the sky up there. What will happen if Berk eats it? Who the hell knows? I turned to the game’s instructions for guidance, but they just say they have “strange effects, either helpful or disastrous” so I guess we’re looking at Trial and Error: The Computer Game with this one.

A little more exploration revealed a corridor full of deadly dangling spiders. I was a having trouble getting Berk past this obstacle, because he’s not the most svelte clay monster out there. You might think Berk would be unconcerned by mere spiders after all the horrors he’s seen, but don’t forget these spiders are falling from the ceiling and Berk’s exposed eyeballs are perched right on top of his body. A spider falling directly onto the surface of your eye is enough to freak anyone out, but not to worry – there’s a way to get past. I can switch to controlling Drutt!

This is Through the Trap Door’s big gameplay change over its predecessor: you can swap between controlling either Berk or Drutt whenever you like, and they’ve got their own unique skills and quirks. Berk can pick up and use items, while Drutt is small enough to avoid many hazards and he can jump.

It’s a good job he can jump, too, because the key’s all the way up there and although Drutt can’t carry the key he can knock it to the ground where some poor blue dope can grab it. However, there’s also a ruddy great bat in this room, and this is where Through the Trap Door reveals itself to be a complete pain in the arse. You need Drutt to jump up and touch the key. That’s simple enough. Videogaming 101. Jump into the thing. But then there’s the bat, who flies down from above and pushes you back down when you try to jump. Okay, so you lure the bat to the right of the screen and then quickly move over and get the key, right? Well, yes, in theory. There are complicating factors, the main one being that Drutt can’t jump that high on his first jump. Or his second, or third. Each time Drutt bounces on the spot he leaps a little higher, so it takes time to reach the correct altitude – so long, in fact, that you can’t just bounce underneath the key because the bat will always swoop down and block you. So, you have to start bouncing on the right of the screen, get some momentum up, wait for the bat to appear, jump to the left and hope you land in the exact right spot underneath the key so you can continue bouncing upwards. Slightly too far to either side of the key? Tough luck, it won’t register as a hit so go back to the start and begin slow, cumbersome process again.

Sounds pretty terrible, doesn’t it? Well buckle your goddamn seatbelt, kid, because it gets worse: Drutt also moves around of his own free will. The moment you let go of the joystick, Drutt will wander off, seemingly at random. I say “seemingly” because often he’s chasing the small worms that appear around the stages, but even when there are no worms about he’ll fidget around and roam the rooms without a care in the world. Any time you’re (nominally) in control of Drutt, you’re wrestling with the controls of a creature that wants to do its own thing and it is infuriating, one of the worst, most wrong-headed game design decisions I’ve ever had the misfortune of experiencing. Imagine playing a Super Mario game but Mario is also controlled, simultaneously, by electrodes wired to the brain of an overstimulated guinea pig, and you’ll get an idea of what trying to perform the extremely precise sequence of events required by this section is like.

Somehow, after countless attempts and a huge amount of unnecessary stress that is bound to cause me health problems later in life, I knocked the key down and nudged it onto the spider screen, where Berk has managed to negotiate the spiders and pick up the key. Now I’ve just got the get to the locked door, but (surprise) there’s a problem.

Berk’s stuck at the bottom of this pit, and the door’s up at the top. Berk can’t jump, or rather I’m sure he can jump but he’s not the type. He’s too stoic and straightforward to be bouncing around like that, so he’s stuck down here unless Drutt can figure something out.

After some more jumping with Drutt, which was still awkward and unpleasant but not nearly as god-awful as reaching the key, I got up near the door. This is where the trial and error really starts to kick in, because all I could think to do was to jump in the various sweets dotted around the level and once they were on the floor to slowly, oh so slowly, nudge them down the pit towards Berk.

Well, that worked. Red sweets give you wings, as the advertising slogan almost goes. Well, you get wings from red sweets in this stage, anyway, and the power of flight comes from other sources later on. There’s absolutely no consistency to what effects each item has, just another way that Through the Trap Door takes what should be a simple puzzle-solving adventure and turns it into a punishing nightmare slog. But Berk’s got the key and he can fly up to the door, so I’ve at least managed to make it through level one. It took longer than you might expect even once I’d solved the puzzles, because I didn’t realise you had to be carrying Drutt before you could move on to the next area. After trying to jump past that bat, I’m sure no-one would blame me for wanting to leave the little bastard behind.

The second stage is a lot more linear but no less aggravating, and Through the Trap Door’s dizzying lack of consistency is never more apparent than in this first screen. You see that hole in the ceiling? There’s a key floating up there, but if Drutt jumps up there he doesn’t knock it down. Instead, a mushroom appears. Berk can eat the mushroom, which allows him to jump. This is a double-edged sword, because while Berk doesn’t jerk around the screen without your input like Drutt does, he’s also a lot, erm, huskier and therefore has even less margin for error when you’re trying to make the very precise jumps over the green monsters that roam the caverns.

Still, after the last stage an activity as simple as “jump over the bad guys” was more than welcome. Berk may be slow, cumbersome, twitchy, imprecise and stuttering in his movements – and he is, as is everything else in the game – but at least I knew what I was supposed to be doing. The stumbling block in this stage was when I found reached a dead end and found this yellow thing and not much else. I think this is supposed to be Bubo, a recurring antagonist – although “irritant” might be a better word – in the show who pops out of the trap door from time to time and generally acts like a little prick. However, in the show Bubo looks like a little prick, with a mean face and general mischievous air, whereas this yellow lump is far more friendly-looking. Maybe this is a member of Bubo’s species who was raised in a loving, nurturing household. Whatever it is, it periodically fires projectiles from the orifice on top of its head. Projectiles that would be perfect for knocking down the key at the beginning of the stage, in fact. But how to get Bubo over there?

It turns out you can pick him up. I know, I didn’t expect to be able to pick up a monster, either. I could only pick up Bubo once Berk had eaten another mushroom, a mushroom that was identical to the first mushroom despite having a wildly different effect. Yeah. So now Berk’s got Bubo in hand, but eating the second mushroom has removed his ability to jump so getting past the deadly monsters in the cavern is going to be tricky. The way you’re supposed to do it is to use Bubo as a mobile gun emplacement of sorts. You place him down, he fires his projectiles into the air, they come down on the monsters and kill them so you can get past. This is where the dread concept of precision once more rears its ugly head. The hitbox for Bubo’s projectiles is tiny, and he fires oh-so-slowly, and the monsters you’re trying to destroy move back and forth, and sometime it just doesn’t bloody work properly even when everything seems to be perfectly aligned. Making it across these three screens becomes the kind of harrowing journey Odysseus would have taken one look at and said “you know what, I think I’ll just live here now” as you laboriously waddle over to Bubo, adjust his position slightly and wait and wait and wait for monster and projectile to align. That’s how you’re supposed to do it, anyway. I used a POKE to turn off the hit detection. I’m kinda dumb, but not a total idiot.

Stage three begins, and that’s a large lead weight. Finally, something recognisable and specific enough that I will surely be able to discern its purpose. Thank you, weight, for being my anchor in this maddening universe. Also this stage appears to be made from snot.

On the next screen, Berk stumbles across an ‘orrible pile of yellow scunge - “scunge” being the deeply evocative word that is used in the show to describe the omnipresent multicoloured slime that is splattered around the castle and often serves as the primary ingredient in Berk’s cooking. What a great word scunge is. I sincerely believe that we should start a campaign to make it an actual word, possibly to describe the stuff you scrape off your oven when you’re cleaning it.

Except, surprise, it’s not scunge but rather a huge and genuinely creepy monster that will eat Berk if he ventures near it. It’s a fun-looking monster, especially those eyes with the trailing optical nerves, although it doesn’t much like it belongs in The Trap Door. That said, one thing I’ll give Through the Trap Door this – the graphics are mostly rather good, especially Berk’s sprite which looks just about as accurate to the show as it’s possible to get on the Spectrum. It’s unfortunate that the backgrounds are mostly pure black, but because the background in the show are a swirling mix of multicoloured patterns it’d be impossible to recreate them on the Spectrum. Impossible without them causing extreme nausea and possible blindness, anyway.

Then, just as things were starting to muddle along in a marginally less painful fashion, Through the Trap Door sets up an astonishingly obnoxious bit of gameplay. Berk needs to get up to the screen above this one, you see, and the only way to do that is to eat a pair of eyes he found on the floor. What, you don’t eat eyeballs you found rolling around on the ground? You think you’re better than Berk, you stuck-up… no, never mind, forget it. The eyeballs themselves aren’t important, what’s important is that eating them makes Berk float upwards like a helium balloon.

And just like a helium balloon, Berk cannot control his own direction, and the lack of air currents in the depths of the trap door mean he’ll only go straight up. This is where Drutt comes in. You have to place Drutt on the small platform at the left of the screen and jump into Berk as he drifts past, pushing him to the right. Oh yes, it all sounds so simple, just like NASA must have thought it sounded simple to point a rocket towards the moon. To accomplish this series of events requires a Herculean effort of will, not just to pull it off but to prevent yourself from ripping the game tape out of your Spectrum, chewing it into fragments with your teeth and spitting the crumbled remains onto a tyre fire.

You start as Drutt, and have him start bouncing so that he’s got enough momentum to reach Berk when the time comes. Make sure he’s as far left as possible, though – if not, he’ll crash into the ceiling and stop bouncing. You can see there’s a tiny hole in the far left of the ceiling to allow Drutt some clearance. I’m not sure whether the programmer only cut out such a small hole due to laziness, ineptitude or sheer contempt for the human concept of “fun,” but there we go. Remember how I said Drutt will move around on his own as soon as you let go of the controls? Well, he’ll also bounce back in the opposite direction if you jump into a wall, so have fun getting the little sod into the exact position required on that minuscule ledge. If you somehow manage that, you have to switch to Berk, make sure he’s in the exact right position, eat the eyes and then quickly switch back to Drutt, praying that you can maintain his bouncing. Berk drifts onto the screen, Drutt jumps towards him and almost invariably misses. Drutt and Berk fall back down, and you have to go through the entire soul-sapping palaver again, fighting the hateful controls every step of the way.

Pictured above: one of roughly twelve thousand failed attempts.

This part of the game honestly made me question what the hell I’m doing with my life. If I put the same amount of effort into something productive or self-improving as I did into try to get two 30-year-old game sprites to bounce into each other, I’d be writing this article from the fifth bedroom of my multi-million pound mansion while the London Philharmonic gently played the Trap Door theme in the background.

I did it, though. I’m not sure how. I think I blacked out for a moment, and then Berk was on the right-hand platform. I’ve never made an emulator save state with such satisfaction in my life.

You reward for making it this far is a short section where you have to pick up worms with glowing coloured lights on their heads and place them into the matching picture frame. It is the sweet ambrosia of the heavens after the last section, even with the annoying bird’s claw that swoops down to grab Berk the instant he stops moving. Frankly, the claw could come down carrying a boombox blasting Nigel Farage’s political speeches and copies of your parent’s boudoir photos and it still wouldn’t spoil the mood. I am the king, the champion, the undefeated, at least until I stop playing the game and realise how much of my precious time on this Earth I have wasted.

I made it to the final stage. I’m not sure how, but I did. See that skull over there, the one that looks identical to Boni because it’s the same sprite that was used for Boni in the intro? Yeah, that’s not Boni. It’s just a skull. A yellow herring, if you will.

No, Boni is actually the skull of this massive skeleton that’s trying to kill Berk with a comically undersized pitchfork. You’re supposed to shoot the skeleton with a cannon until Boni is knocked loose, a scenario which raises all sorts of questions. Like, is this fair on Boni? Maybe he wants to be part of a full skeleton. It must be a nice change of pace from being an immobile skull that Berk has to drag around in a little cart. On the other hand, although Boni is a grumpy sort who likes to complain, I don’t think he’d ever resort to trying to murder Berk, so I have to assume he’s not in control of the skeleton.

When I reached this point – Berk trapped in a pit, harassed by ghosts and snakes, surrounded by sausages – I knew it was time to admit defeat. Even with guides to hand and various cheats at my disposal, I simply could not bear to continue with Through the Trap Door. The hideous controls, the glacial pace, the fiddliness, all of it became too much. Imagine trying to build an Airfix kit while wearing oven gloves and you’ve got some idea of what it’s like trying to play this game. I looked up the game’s ending, and all that happens is the three friends return to the opening screen while a text box reading “Home Sweet Home” appears, so at least I’m not missing out on much.

Apart from the addition of Drutt as a second playable character, an idea which I admit could have had legs (six of them, even), Through the Trap Door is a real disappointment of a sequel. The first Trap Door game wasn’t good but at least it was interesting and had some potential, but for the sequel to take the exact same gameplay mechanics, concepts and sprites and turn them into such an awkward mess is very disappointing. I can see how this could be a good game, even: trial and error is not necessarily a bad way to figure out puzzles, as long as you’ve got some guidance and, more importantly, you can try again quickly. Through the Trap Door’s biggest failing is that whenever you screw up, the grinding tedium of getting back to where you were is enough to put anyone off.

So, like I say, it’s a real shame. If there was a proper Lucasarts-style graphics adventure based on The Trap Door, with the kind of cartoony graphics you’d find in, say, Day of the Tentacle, then that would be one of my dream games – but instead I’m stuck with this nightmare. Oh well, I can always go and watch the show. You should do the same.

25/02/2017

21/02/2017

CHUCK ROCK (MEGADRIVE / GENESIS)

It’s a shame that most videogame-to-movie adaptations are terrible, because I think a big-screen version of today’s game would be worth making. Of course, that’s only because then you’d be able to use the tagline “Fun is just a stone’s throw away” on the posters. It’s the 1992 Megadrive version of Core Design’s prehistoric platformer Chuck Rock!

Originally released in 1991 for the Amiga and Atari ST, Chuck Rock was soon ported to a wide number of different platforms. So why the Megadrive version? No real reason, it just looks very close to the original but is controlled with a pad with extra buttons.

So, the title screen, then. There’s a band playing. I’m sure we’ve all already made a mental “rock band” pun, so let’s skip that and say hey, the animations of the band are actually synced up to the music somewhat, which is a nice touch. From left to right you’ve got a dinosaur in a wig, a drummer with the Virgin logo on his kit, (because Virgin published this version of the game,) Chuck Rock himself (who is also wearing a wig, as we shall see in a moment) and Chuck’s, erm, buxom wife Ophelia. The Megadrive version goes straight into the action when you press start, although other versions do have an introductory cutscene. The story is that Ophelia is kidnapped and Chuck sets out to rescue her. So far, so exactly the same as 90% of other 16-bit platformers. However, the cutscene shows that Ophelia was abducted by the band’s drummer, whose name is Gary Gritter. Yes, he’s named after and is physically based on former glam-rock singer and current incarcerated paedophile Gary Glitter, making this the second game I’ve played in the past few months to feature the same bit of extremely unfortunate celebrity caricature.

Chuck Rock is a platformer, that much is clear. You jump a lot in this game, as well as avoiding enemies where you can. There are a couple of twists to the formula: for starters, there don’t seem to be any bottomless pits for you to fall into. Some of the pits are filled with lava or spikes, but they all have a bottom. Chuck can also attack, either with a jumping kick or, if he’s standing on solid ground, by thrusting his fat gut at the bad guys. Whether the enemies perish from sheer disgust as a sweaty caveman’s belly rubs up against them remains unconfirmed, but the problem with this attack is obvious: it has almost no range. Like, Chuck’s a fairly chunky chap but even his prodigious gut doesn’t reach as far as his fists would. And anyway, what kind of caveman doesn’t carry a club? You’re a disgrace to the uniform, Chuck.

The look of Chuck Rock is unmistakeably European, isn’t it? Cartoonish without a hint of manga influence, like an alternate version of The Flintstones that started in the pages of The Beano. It’s a good look, though. Nice and colourful, pleasingly solid and detailed sprites, it definitely looks the part.

And now, the secret of Chuck Rock’s title is revealed: he’s called Chuck Rock because he can chuck rocks. Pick ‘em up, set ‘em down, carry ‘em around and throw them at dinosaurs and other dangerous fauna. Rocks: nature’s Swiss Army knife. There are two sizes of rock, small and big, and each kind slows Chuck down either a little or a lot while he’s carrying them. The benefits of carrying a rock, not including “a great upper body workout,” are that when they’re over Chuck’s head they can protect him from aerial attacks, and if a flying enemy crashes into them they will die. Plus you can throw them at things, which is generally much more effective than the gut-bounce. As well as that, the rocks can be used as platforms, either for a little extra height when reaching distant platforms or as a stepping-stone when placed on hazardous floors. It’s a very welcome bit of extra gameplay in what would be a pretty by-the-numbers platforming adventure otherwise.

Not all the creatures are out to kill Chuck. Some of them are actively helpful, like this pterodactyl that carries him across the screen. Now, a confession: I have, in the past, mentioned Sega’s “Cyber Razor Cut” series of TV ads for the Megadrive, and specifically I’ve said that the line “hitch a lift on a pterodac-bird” is one of the worst attempted rhymes I’ve ever heard. However, having listened to the ad again in slightly better quality, I concede that the actual line might be “pterodactyl,” only the pronunciation of the word has been cruelly, viciously mangled in an attempt to get it to rhyme with “world.” It does not rhyme. I think I preferred it when I thought it said “pterodac-bird.”

As I say, the Megadrive version of Chuck Rock is mostly identical to the original computer games, but here’s something that’s different: in the Amiga version, this huge dinosaur tried to take an actual shit on Chuck’s head when he walks underneath it. I remembered this from having played the Amiga version as a kid, and when you are a kid a massive dinosaur taking a dump on your character is the kind of thing that sticks in the memory. Sadly, this does not happen in the Megadrive version, and I can only assume it was removed for reasons of perceived good taste.

And so on you go, guiding Chuck through the jungle setting dispatching dinosaurs with his paunch and occasionally throwing boulders onto crocodile’s heads so you can use them as see-saws to propel you upwards. Unfortunately the crocodiles don’t say “it’s a living!” when you do this, probably because you’ve just dropped a rock on their heads.

It’s all very jolly, and certainly feels as though it’s had a little more craft put into it, a little more love and affection spent, than you might find in the slew of generic run-n-jump platformers of the time. Apart from Chuck having a slight (but manageable) delay on his jumps, it all controls very nicely and hits a good balance of simple, obvious challenges you need to clear in order to progress and hidden areas that require a bit more exploration and boulder-stacking to access. You only really get point items from these side areas, but it’s still fun to see where you can get to.

After a while, Chuck stumbles upon the first boss. It’s an angry triceratops, charging back and forth along the bottom of the screen. There’s a rock down there, too, and your task becomes clear: jump down while the triceratops is at the far end of the screen, grab the rock, climb back up the platforms and then throw the rock onto the triceratops from above like a moronic yob throwing bricks off a motorway bridge onto the cars below. It’s an easy task to accomplish, so it’s a shame that you have to do it a bunch of times to defeat the triceratops. Yes, this fight falls into my least favourite category of boss fight – the one where you do the same basic action over and over. The triceratops doesn’t change its attack patterns or anything like that, so basically the fight is saying “sure, you dropped a rock on a dinosaur once, but can you do the exact same thing ten times?!” Yes, Chuck Rock, yes I can. If I take any damage, it’s because I got bored and my mind started to wander.

Stage two takes place in some caves, every surface covered in slimy, gloopy mud. I sincerely hope it’s mud, anyway. The caves feature many of the cave-based hazards you might expect from a 16-bit platformers, like dangerous stalagmites, falling rocks and scuttling spiders, as seen above. These spiders remind me of the monster version of Drutt from the “Nasty Stuff” episode of classic kid’s claymation show Trap Door, a reference so specific even I’m surprised it sprang to my mind.

Halfway through the stage there’s a lava section, because of course there is. Interestingly, Chuck responds to falling into molten rock the same way Mario does in the 3D Super Mario games – rather than being immediately incinerated, he leaps back out of the magma with a yelp and an accompanying loss of health, furthering Chuck Rock’s status as a platformer that is completely disinterested in killing the platformer by having them fall into bottomless chasms.

There are a few elevators in this stage, powered by dinosaurs running around treadmills, and once you’re off the lift the dinosaurs lie down and have a kip. There are quite a few fun little flourishes like this in Chuck Rock, all of which help elevate it above the average in terms of presentation if not gameplay.

Boss number two is a sabre-toothed tiger. A fearsome foe indeed, made all the more dangerous by the lack of any rocks in the arena that you can chuck at it. This means you have to rely on Chuck’s jumping kicks and belly-bounces, both of which have a range measured in nanometres and are thus ill suited to fighting something with teeth bigger than your head. Most of the damage you’ll take in this fight comes from being unable to halt Chuck’s forward momentum as he attacks, often propelling him straight into the tiger. On top of that, the tiger can also roar, which momentarily freezes Chuck in place through sheer terror. His jaw drops and his skin grows pale, which again is a lovely little touch.

The tiger runs around the arena in a loop, lunging at Chuck when he gets near. My strategy? I didn’t really have one until I managed to get behind the tiger and trap it against that small lip of rock on the left of the screen. Once it was there, I mashed the attack button as far as I could, grinding the tiger to death between a rock and soft, flabby place. A flukey victory, sure, but I’ll take it.

Oh joy, it’s an underwater stage, everyone loves those. A completely different set of physical rules to grapple with, the action rather hampered by the Megadrive’s lack of transparency effects? What’s not to love? Okay, I’m being too harsh there. The swimming portions of Chuck Rock aren’t that bad. It certainly helps that Chuck still moves pretty quickly when he’s submerged, which keeps the game flowing, and half of the stage takes place on land anyway. It’s a lot more awkward to defeat enemies while you’re underwater, as you can probably imagine, but we should commend Chuck for his bravery. He’s not afraid to kick a Portuguese man-o-war to death with his bare feet, whereas I feel queasy if I step on spilled shampoo in the shower.

While the underwater sections aren’t terrible, it’s still preferable to ride over them on the back of a friendly whale.

One annoying facet of Chuck Rock’s level design is that it features far too many blind jumps. Here, for example, the only way to progress was to jump off a cliff (a phrase that looks weird now I’ve written it out) into the water below. The thing is, you can’t see the water below, which is why Chuck’s about to take damage from landing on a jellyfish. Each stage seems to include at least a couple of blind jumps, and the longer I write about videogames the more irritating I find this situation. I like to delude myself that if I can see the danger, I can use my skill to avoid it, even if that’s rarely true.

Stage three follows up some not-especially-inspired level design with an absolutely terrible boss in the form of this plesiosaur. If the Loch Ness monster was a huge dork, this is what it’d look like, snorkel and all. All it does is bob up and down and occasionally blow bubbles at you. These are videogame bubbles and therefore they hit with the force of a .44 magnum round, but they’re still easy to avoid and all you need do to defeat this boss is find the precise distance from which you can float in place and kick it repeatedly without bumping into it. It feels less like a fight and more like synchronised swimming, and even more like a waste of everyone’s goddamn time.

Stage four combines the swimming sections with the almost mandatory ice stage, complete with slippery platforms and frozen enemies. It’s a testament to the overall craft of Chuck Rock that the combination of these two tropes, probably the least-loved of all platformer level types, somehow remains fairly fun to play. It’s not perfect, and in a lot of ways it’s a backward step from earlier areas: there seems to be less emphasis on creative rock throwing, and the increased difficulty level comes from packing more and more creatures into each screen rather than through thoughtful level design. Still, it looks really nice, and I love these ice-crystal backgrounds and the dinosaurs that attack by sliding across the platforms while encased in massive ice cubes.

I also love these snowball-throwing dinosaurs, because they are utterly adorable, slinging their snowballs with a real sense of childlike innocence. It’s a real shame what Chuck’s about to do to it with this large rock, honestly.

This stage also has a brief outdoor section, complete with snowmen that I’m going to assume were made by those same dinosaurs that throw the snowballs. A bunch of them got together and built a snowman, and it’s cute as heck. “If they’re dinosaurs, why didn’t the build a snow-dinosaur, then?” I hear you ask, and the answer is because making a snow dinosaur would be a lot more difficult, especially if you don’t have opposable thumbs, obviously.

Atop a cold and snowy mountain, Chuck faces off against a woolly mammoth in a fight that’s quite similar to the underwater one but vastly improved by taking place on land. The mammoth charges, so you jump up and kick it right in the face. Sometimes it’ll use its trunk to fire snowballs or to suck you towards it, vacuum-cleaner style. I’m standing by my statement that this is a better boss fight than the last one, but it’s still not good, and none of Chuck Rock’s end-of-stage encounters are much fun to endure. They’re the weakest part of the game, that’s for sure, at once boringly simply yet made frustrating by the incredibly short range of Chuck’s attacks.

Let’s look on the bright side, though. All this snow and ice implies that if I just hang around for a while, I won’t have to fight any more dinosaurs. After all, as a giant Austrian once said “what killed the dinosaurs? The Ice Age!”

Oh. Wow. I didn’t expect all the dinosaurs to actually die. I mean, I know Chuck’s thrown rocks at a lot of them, but not enough to cause the mass extinction event that makes up the final stage. It really must be the Ice Age’s doing.

There are even dinosaur graves, complete with dinosaur headstones, just in case you though this cheerful cartoon romp was getting a bit too cheerful. Chuck is too respectful of the dead to pick up the gravestone and throw it, which is disappointing because I like the irony of beating someone to death with a tombstone.

As with the previous stage, this boneyard suffers from an overabundance of enemies packed into each screen, which makes progressing just enough of a slog that you begin to wonder whether you’re still having fun. At least the enemies themselves are fun, with rattling skeletons and dinosaur mummies charging around the place, and the enemy designs are definitely one of Chuck Rock’s strong points. I especially like the way basic enemies change as you make your way through the game: for instance, the hostile pterodactyls behave in the same way throughout the game, but in the snowy levels they gain a little scarf and in this stage they’re skeletons, and that goes a long way towards making them feel less repetitive.

Here, Chuck breaks the cardinal rule of the Caveman Code by walking directly into a dinosaur’s mouth. Don’t worry, though, the dinosaur is already dead, or at least extremely unwell. All its teeth fall out when you approach it, so there’s no worries about being chewed to death.

This means the next area takes place inside a dinosaur, which is great even if it is full of these disturbingly cheerful hearts. There are dozens of the bloody things in here, so they can’t be the dinosaur’s heart and are presumably a species of parasitic organism that invades other living creatures until their innards resemble the bins behind Poundland on the day after Valentine’s.

I’ve always loved videogame levels that take place inside a living creature, you know. I think it’s the cross-pollination of the bio-organic settings of my beloved Alien franchise, the NES version of Life Force / Salamander and the “In The Flesh” level from Blood. Chuck Rock gets an extra point from me for including such a stage.

Then, with surprising suddenness, the final boss appears. Notice that I am no longer inside the dinosaur. I assume Chuck managed to leave the corpse via the, ahem, most obvious exit. I think by this point it’s fair to say that Chuck has been through some (literal) serious shit, so a dinosaur wearing boxing gloves and a super-sized version of Sir Arthur’s boxers is unlikely to faze him. I do like the dinosaur’s little crown, mind you.

Anyway, the dinosaur will try to attack you in different ways depending on which platform you’re standing on, either with punches or by biting. You’d think the punches would be the least effective of these attacks, what with the boss having stubby little T. Rex arms, but I had far more success on the top platform. The boss comes in for a bite, Chuck boots it in the snout, repeat until the game finishes. Did I mention boss battles aren’t exactly Chuck Rock’s strong point?

Thus the game ends: Chuck is reunited with his wife, and… hang on, so that dinosaur is Gary? I thought I was after the human kidnapper Gary Gritter? What the heck is going on? In search of answers, I checked out the ending to the Amiga version, where I noticed this:

If you look at the ending image without the text in the way, you can see that someone has been crushed by the dinosaur’s falling body. I guess that’s Gary, then. You can understand my confusion, given that Gary doesn’t appear in the final boss’ room or anything, but apparently he was there the entire time. What a lame ending, made worse by the fact I was momentarily led to believe I’d just fought a T. Rex called Gary only to have such a wonderful notion cruelly snatched away from me.

Before we leave Chuck Rock for good, take another look at the ending text, specifically the line about how “Chuck can not wait to get home and out of his leaves.” A couple of points: for starters, the first time I read it I assumed “get out of his leaves” was a euphemism for getting extremely drunk. You know, “Chuck necked a bottle of scotch and got absolutely out of his leaves, started a fight with a bouncer and dropped his kebab,” that kind of thing. Sadly that’s not the case, “his leaves” actually means the foliage Chuck’s wearing as under (and indeed outer) wear. Also, in the console versions it says he’s going on vacation after this ordeal, which is fair enough. However, in the original versions it’s strongly implied that he’s going home to have sex with his wife, which is also fair enough but apparently far too racy for the Sega Megadrive.

Amid the great morass of cartoony 16-bit platformers, Chuck Rock can stand tall as one that’s distinctly above average, especially for one based on a computer game. Sadly it doesn’t quite reach the top thanks to the dull boss battles, too-frequent blind jumps and a rock-throwing mechanic that’s underutilized in the later stages. Presentation-wise it’s very good, with lots of charming (and charmingly weird) monsters and backdrops, plus an enjoyable soundtrack that’s been expanded from the single tune of the original to a track for each level. I’m especially fond of the eminently hummable and extremely bouncy stage two theme. Overall, then, time with Chuck Rock was time well spent. Okay, maybe not well spent. I could have done a lot of chores instead of listening to Chuck shout “unga bunga!” but it was, mostly, fun. I’m still disappointed that dinosaur wasn’t called Gary, though.

Originally released in 1991 for the Amiga and Atari ST, Chuck Rock was soon ported to a wide number of different platforms. So why the Megadrive version? No real reason, it just looks very close to the original but is controlled with a pad with extra buttons.

So, the title screen, then. There’s a band playing. I’m sure we’ve all already made a mental “rock band” pun, so let’s skip that and say hey, the animations of the band are actually synced up to the music somewhat, which is a nice touch. From left to right you’ve got a dinosaur in a wig, a drummer with the Virgin logo on his kit, (because Virgin published this version of the game,) Chuck Rock himself (who is also wearing a wig, as we shall see in a moment) and Chuck’s, erm, buxom wife Ophelia. The Megadrive version goes straight into the action when you press start, although other versions do have an introductory cutscene. The story is that Ophelia is kidnapped and Chuck sets out to rescue her. So far, so exactly the same as 90% of other 16-bit platformers. However, the cutscene shows that Ophelia was abducted by the band’s drummer, whose name is Gary Gritter. Yes, he’s named after and is physically based on former glam-rock singer and current incarcerated paedophile Gary Glitter, making this the second game I’ve played in the past few months to feature the same bit of extremely unfortunate celebrity caricature.

Chuck Rock is a platformer, that much is clear. You jump a lot in this game, as well as avoiding enemies where you can. There are a couple of twists to the formula: for starters, there don’t seem to be any bottomless pits for you to fall into. Some of the pits are filled with lava or spikes, but they all have a bottom. Chuck can also attack, either with a jumping kick or, if he’s standing on solid ground, by thrusting his fat gut at the bad guys. Whether the enemies perish from sheer disgust as a sweaty caveman’s belly rubs up against them remains unconfirmed, but the problem with this attack is obvious: it has almost no range. Like, Chuck’s a fairly chunky chap but even his prodigious gut doesn’t reach as far as his fists would. And anyway, what kind of caveman doesn’t carry a club? You’re a disgrace to the uniform, Chuck.

The look of Chuck Rock is unmistakeably European, isn’t it? Cartoonish without a hint of manga influence, like an alternate version of The Flintstones that started in the pages of The Beano. It’s a good look, though. Nice and colourful, pleasingly solid and detailed sprites, it definitely looks the part.

And now, the secret of Chuck Rock’s title is revealed: he’s called Chuck Rock because he can chuck rocks. Pick ‘em up, set ‘em down, carry ‘em around and throw them at dinosaurs and other dangerous fauna. Rocks: nature’s Swiss Army knife. There are two sizes of rock, small and big, and each kind slows Chuck down either a little or a lot while he’s carrying them. The benefits of carrying a rock, not including “a great upper body workout,” are that when they’re over Chuck’s head they can protect him from aerial attacks, and if a flying enemy crashes into them they will die. Plus you can throw them at things, which is generally much more effective than the gut-bounce. As well as that, the rocks can be used as platforms, either for a little extra height when reaching distant platforms or as a stepping-stone when placed on hazardous floors. It’s a very welcome bit of extra gameplay in what would be a pretty by-the-numbers platforming adventure otherwise.

Not all the creatures are out to kill Chuck. Some of them are actively helpful, like this pterodactyl that carries him across the screen. Now, a confession: I have, in the past, mentioned Sega’s “Cyber Razor Cut” series of TV ads for the Megadrive, and specifically I’ve said that the line “hitch a lift on a pterodac-bird” is one of the worst attempted rhymes I’ve ever heard. However, having listened to the ad again in slightly better quality, I concede that the actual line might be “pterodactyl,” only the pronunciation of the word has been cruelly, viciously mangled in an attempt to get it to rhyme with “world.” It does not rhyme. I think I preferred it when I thought it said “pterodac-bird.”

As I say, the Megadrive version of Chuck Rock is mostly identical to the original computer games, but here’s something that’s different: in the Amiga version, this huge dinosaur tried to take an actual shit on Chuck’s head when he walks underneath it. I remembered this from having played the Amiga version as a kid, and when you are a kid a massive dinosaur taking a dump on your character is the kind of thing that sticks in the memory. Sadly, this does not happen in the Megadrive version, and I can only assume it was removed for reasons of perceived good taste.

And so on you go, guiding Chuck through the jungle setting dispatching dinosaurs with his paunch and occasionally throwing boulders onto crocodile’s heads so you can use them as see-saws to propel you upwards. Unfortunately the crocodiles don’t say “it’s a living!” when you do this, probably because you’ve just dropped a rock on their heads.

It’s all very jolly, and certainly feels as though it’s had a little more craft put into it, a little more love and affection spent, than you might find in the slew of generic run-n-jump platformers of the time. Apart from Chuck having a slight (but manageable) delay on his jumps, it all controls very nicely and hits a good balance of simple, obvious challenges you need to clear in order to progress and hidden areas that require a bit more exploration and boulder-stacking to access. You only really get point items from these side areas, but it’s still fun to see where you can get to.

After a while, Chuck stumbles upon the first boss. It’s an angry triceratops, charging back and forth along the bottom of the screen. There’s a rock down there, too, and your task becomes clear: jump down while the triceratops is at the far end of the screen, grab the rock, climb back up the platforms and then throw the rock onto the triceratops from above like a moronic yob throwing bricks off a motorway bridge onto the cars below. It’s an easy task to accomplish, so it’s a shame that you have to do it a bunch of times to defeat the triceratops. Yes, this fight falls into my least favourite category of boss fight – the one where you do the same basic action over and over. The triceratops doesn’t change its attack patterns or anything like that, so basically the fight is saying “sure, you dropped a rock on a dinosaur once, but can you do the exact same thing ten times?!” Yes, Chuck Rock, yes I can. If I take any damage, it’s because I got bored and my mind started to wander.

Stage two takes place in some caves, every surface covered in slimy, gloopy mud. I sincerely hope it’s mud, anyway. The caves feature many of the cave-based hazards you might expect from a 16-bit platformers, like dangerous stalagmites, falling rocks and scuttling spiders, as seen above. These spiders remind me of the monster version of Drutt from the “Nasty Stuff” episode of classic kid’s claymation show Trap Door, a reference so specific even I’m surprised it sprang to my mind.

Halfway through the stage there’s a lava section, because of course there is. Interestingly, Chuck responds to falling into molten rock the same way Mario does in the 3D Super Mario games – rather than being immediately incinerated, he leaps back out of the magma with a yelp and an accompanying loss of health, furthering Chuck Rock’s status as a platformer that is completely disinterested in killing the platformer by having them fall into bottomless chasms.

There are a few elevators in this stage, powered by dinosaurs running around treadmills, and once you’re off the lift the dinosaurs lie down and have a kip. There are quite a few fun little flourishes like this in Chuck Rock, all of which help elevate it above the average in terms of presentation if not gameplay.

Boss number two is a sabre-toothed tiger. A fearsome foe indeed, made all the more dangerous by the lack of any rocks in the arena that you can chuck at it. This means you have to rely on Chuck’s jumping kicks and belly-bounces, both of which have a range measured in nanometres and are thus ill suited to fighting something with teeth bigger than your head. Most of the damage you’ll take in this fight comes from being unable to halt Chuck’s forward momentum as he attacks, often propelling him straight into the tiger. On top of that, the tiger can also roar, which momentarily freezes Chuck in place through sheer terror. His jaw drops and his skin grows pale, which again is a lovely little touch.

The tiger runs around the arena in a loop, lunging at Chuck when he gets near. My strategy? I didn’t really have one until I managed to get behind the tiger and trap it against that small lip of rock on the left of the screen. Once it was there, I mashed the attack button as far as I could, grinding the tiger to death between a rock and soft, flabby place. A flukey victory, sure, but I’ll take it.

Oh joy, it’s an underwater stage, everyone loves those. A completely different set of physical rules to grapple with, the action rather hampered by the Megadrive’s lack of transparency effects? What’s not to love? Okay, I’m being too harsh there. The swimming portions of Chuck Rock aren’t that bad. It certainly helps that Chuck still moves pretty quickly when he’s submerged, which keeps the game flowing, and half of the stage takes place on land anyway. It’s a lot more awkward to defeat enemies while you’re underwater, as you can probably imagine, but we should commend Chuck for his bravery. He’s not afraid to kick a Portuguese man-o-war to death with his bare feet, whereas I feel queasy if I step on spilled shampoo in the shower.

While the underwater sections aren’t terrible, it’s still preferable to ride over them on the back of a friendly whale.

One annoying facet of Chuck Rock’s level design is that it features far too many blind jumps. Here, for example, the only way to progress was to jump off a cliff (a phrase that looks weird now I’ve written it out) into the water below. The thing is, you can’t see the water below, which is why Chuck’s about to take damage from landing on a jellyfish. Each stage seems to include at least a couple of blind jumps, and the longer I write about videogames the more irritating I find this situation. I like to delude myself that if I can see the danger, I can use my skill to avoid it, even if that’s rarely true.

Stage three follows up some not-especially-inspired level design with an absolutely terrible boss in the form of this plesiosaur. If the Loch Ness monster was a huge dork, this is what it’d look like, snorkel and all. All it does is bob up and down and occasionally blow bubbles at you. These are videogame bubbles and therefore they hit with the force of a .44 magnum round, but they’re still easy to avoid and all you need do to defeat this boss is find the precise distance from which you can float in place and kick it repeatedly without bumping into it. It feels less like a fight and more like synchronised swimming, and even more like a waste of everyone’s goddamn time.

Stage four combines the swimming sections with the almost mandatory ice stage, complete with slippery platforms and frozen enemies. It’s a testament to the overall craft of Chuck Rock that the combination of these two tropes, probably the least-loved of all platformer level types, somehow remains fairly fun to play. It’s not perfect, and in a lot of ways it’s a backward step from earlier areas: there seems to be less emphasis on creative rock throwing, and the increased difficulty level comes from packing more and more creatures into each screen rather than through thoughtful level design. Still, it looks really nice, and I love these ice-crystal backgrounds and the dinosaurs that attack by sliding across the platforms while encased in massive ice cubes.

I also love these snowball-throwing dinosaurs, because they are utterly adorable, slinging their snowballs with a real sense of childlike innocence. It’s a real shame what Chuck’s about to do to it with this large rock, honestly.

This stage also has a brief outdoor section, complete with snowmen that I’m going to assume were made by those same dinosaurs that throw the snowballs. A bunch of them got together and built a snowman, and it’s cute as heck. “If they’re dinosaurs, why didn’t the build a snow-dinosaur, then?” I hear you ask, and the answer is because making a snow dinosaur would be a lot more difficult, especially if you don’t have opposable thumbs, obviously.

Atop a cold and snowy mountain, Chuck faces off against a woolly mammoth in a fight that’s quite similar to the underwater one but vastly improved by taking place on land. The mammoth charges, so you jump up and kick it right in the face. Sometimes it’ll use its trunk to fire snowballs or to suck you towards it, vacuum-cleaner style. I’m standing by my statement that this is a better boss fight than the last one, but it’s still not good, and none of Chuck Rock’s end-of-stage encounters are much fun to endure. They’re the weakest part of the game, that’s for sure, at once boringly simply yet made frustrating by the incredibly short range of Chuck’s attacks.

Let’s look on the bright side, though. All this snow and ice implies that if I just hang around for a while, I won’t have to fight any more dinosaurs. After all, as a giant Austrian once said “what killed the dinosaurs? The Ice Age!”

Oh. Wow. I didn’t expect all the dinosaurs to actually die. I mean, I know Chuck’s thrown rocks at a lot of them, but not enough to cause the mass extinction event that makes up the final stage. It really must be the Ice Age’s doing.

There are even dinosaur graves, complete with dinosaur headstones, just in case you though this cheerful cartoon romp was getting a bit too cheerful. Chuck is too respectful of the dead to pick up the gravestone and throw it, which is disappointing because I like the irony of beating someone to death with a tombstone.

As with the previous stage, this boneyard suffers from an overabundance of enemies packed into each screen, which makes progressing just enough of a slog that you begin to wonder whether you’re still having fun. At least the enemies themselves are fun, with rattling skeletons and dinosaur mummies charging around the place, and the enemy designs are definitely one of Chuck Rock’s strong points. I especially like the way basic enemies change as you make your way through the game: for instance, the hostile pterodactyls behave in the same way throughout the game, but in the snowy levels they gain a little scarf and in this stage they’re skeletons, and that goes a long way towards making them feel less repetitive.

Here, Chuck breaks the cardinal rule of the Caveman Code by walking directly into a dinosaur’s mouth. Don’t worry, though, the dinosaur is already dead, or at least extremely unwell. All its teeth fall out when you approach it, so there’s no worries about being chewed to death.

This means the next area takes place inside a dinosaur, which is great even if it is full of these disturbingly cheerful hearts. There are dozens of the bloody things in here, so they can’t be the dinosaur’s heart and are presumably a species of parasitic organism that invades other living creatures until their innards resemble the bins behind Poundland on the day after Valentine’s.

I’ve always loved videogame levels that take place inside a living creature, you know. I think it’s the cross-pollination of the bio-organic settings of my beloved Alien franchise, the NES version of Life Force / Salamander and the “In The Flesh” level from Blood. Chuck Rock gets an extra point from me for including such a stage.

Then, with surprising suddenness, the final boss appears. Notice that I am no longer inside the dinosaur. I assume Chuck managed to leave the corpse via the, ahem, most obvious exit. I think by this point it’s fair to say that Chuck has been through some (literal) serious shit, so a dinosaur wearing boxing gloves and a super-sized version of Sir Arthur’s boxers is unlikely to faze him. I do like the dinosaur’s little crown, mind you.

Anyway, the dinosaur will try to attack you in different ways depending on which platform you’re standing on, either with punches or by biting. You’d think the punches would be the least effective of these attacks, what with the boss having stubby little T. Rex arms, but I had far more success on the top platform. The boss comes in for a bite, Chuck boots it in the snout, repeat until the game finishes. Did I mention boss battles aren’t exactly Chuck Rock’s strong point?

Thus the game ends: Chuck is reunited with his wife, and… hang on, so that dinosaur is Gary? I thought I was after the human kidnapper Gary Gritter? What the heck is going on? In search of answers, I checked out the ending to the Amiga version, where I noticed this:

If you look at the ending image without the text in the way, you can see that someone has been crushed by the dinosaur’s falling body. I guess that’s Gary, then. You can understand my confusion, given that Gary doesn’t appear in the final boss’ room or anything, but apparently he was there the entire time. What a lame ending, made worse by the fact I was momentarily led to believe I’d just fought a T. Rex called Gary only to have such a wonderful notion cruelly snatched away from me.

Before we leave Chuck Rock for good, take another look at the ending text, specifically the line about how “Chuck can not wait to get home and out of his leaves.” A couple of points: for starters, the first time I read it I assumed “get out of his leaves” was a euphemism for getting extremely drunk. You know, “Chuck necked a bottle of scotch and got absolutely out of his leaves, started a fight with a bouncer and dropped his kebab,” that kind of thing. Sadly that’s not the case, “his leaves” actually means the foliage Chuck’s wearing as under (and indeed outer) wear. Also, in the console versions it says he’s going on vacation after this ordeal, which is fair enough. However, in the original versions it’s strongly implied that he’s going home to have sex with his wife, which is also fair enough but apparently far too racy for the Sega Megadrive.

Amid the great morass of cartoony 16-bit platformers, Chuck Rock can stand tall as one that’s distinctly above average, especially for one based on a computer game. Sadly it doesn’t quite reach the top thanks to the dull boss battles, too-frequent blind jumps and a rock-throwing mechanic that’s underutilized in the later stages. Presentation-wise it’s very good, with lots of charming (and charmingly weird) monsters and backdrops, plus an enjoyable soundtrack that’s been expanded from the single tune of the original to a track for each level. I’m especially fond of the eminently hummable and extremely bouncy stage two theme. Overall, then, time with Chuck Rock was time well spent. Okay, maybe not well spent. I could have done a lot of chores instead of listening to Chuck shout “unga bunga!” but it was, mostly, fun. I’m still disappointed that dinosaur wasn’t called Gary, though.

Labels:

chuck rock,

core design,

genesis,

megadrive,

platformer,

virgin

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)