The name’s X. Agent X, and he’s here to do all the things James Bond would, apart from dressing as a clown and making sexual advances towards women with contrived names. That’s right, it’s Mastertronic and Software Creation’s 1986 ZX Spectrum cartoon-espionage-em-up Agent X!

Or Agent X in The Brain Drain Caper, as the title screen would have it. That title doesn’t make much sense, because there’s no “brain drain” going on in this one. It’s about a mad scientist who has kidnapped the US president, not Soviet scientists defecting to the West. Unless the title is intended as a warning that this game is so dumb that playing it will actually make you less intelligent. I really hope that’s not the case.

Early impressions are mixed. I like the artwork on the loading screen, which promises an adventure filled with comic-book action and very eighties supercars, but the title screen has music and it’s fair to say I’m divided on its merits. It was composed by game music legend Tim Follin, and the composition itself is good. It’s a shame, then, that the music is being created by a ZX Spectrum, because that means it sounds like it’s being played by a symphony orchestra of ants on tiny, ant-sized vacuum cleaners. It is a technically remarkable feat of sound engineering, given the limitations of the technology it appears on, but it’s difficult to listen to for long.

You’re thrown straight into the action with the first stage, a high-speed motorway chase in which Agent X – that’s his sports car in the middle – must drive forwards for a while. Until the “Distance” bar on the right is full, in fact. Obviously it’s not that simple, because all the other cars on the road seem to have wandered their way in from a Mad Max game, and they’ll do their darnedest to nudge and bump your car around the road.

This is a problem, because both the edge of the road and certain sections of the road itself, like the chequerboard-patterned area above, will cause your car to explode if you come into contact with them. So, you know, don’t do that. Instead, you should use the fact that your car is just as good at nudging as the others to push your foes into these obstacles. That way, they explode and you get points. Is there much reason to collect points? No, but seeing your attackers blow up because you shunted them into a barrier is a reward in itself. You just have make sure you watch out for the tanks, which cannot be nudged.

If you’re feeling especially bold, you can try jumping over the obstacles. Of course you can, the ability to jump over obstacles is second only to mounted machine guns when it comes to gadgets on a James Bond-esque supercar. However, avoiding the obstacles entirely is by far the safer option, mostly because there’s a distinct delay between pushing the jump button and your car leaving the tarmac. This is really the only wrinkle in this stage, which on the whole is rather good fun. Jumps aside, your car controls smoothly enough that you can nimbly dash through gaps, the collision detection is excellent, the impacts and their effects are consistent and there’s even some effort to differentiate between the types of cars on the road – for instance, the police cars will try to drive in front of you and block you off. It’s a solid slice of arcade driving action, made more enjoyable by the crisp, cartoony graphics.

Forget all that, though: my absolute favourite thing I noticed about this stage (and probably my favourite thing in the whole game) is your lives counter. Rather than having a standard numerical indicator showing how much more punishment Agent X can take, instead there’s a small display on the bottom-right. Every time you lose a life, Agent X literally takes one step closer to the grave. As someone with a fairly macabre sense of humour, this is wonderful and could only be improved if, upon reaching his tombstone, Agent X dug himself a shallow grave and jumped into it, pulling the turf over his head like a blanket.

Once you’ve driven far enough to fill the distance meter, Agent X arrives at the sinister Omega Base. Note that it’s “sinister”, not “secret.” It’s difficult to keep a location secret when there’s a busy highway that leads right to the front door.

Now the action shifts to a complete different genre – it’s a side-scrolling, single-plane brawler! Here we get our first proper look at Agent X himself in action. No, I’m not counting his solemn, dignified march towards his own mortality as “in action.” He’s not quite the James Bond type you might expect from the game’s premise and its box art. He’s more of a hard-boiled gumshoe meets Andy Capp sort, his hat pulled down tight and a cigarette forever bobbing at the corner of his mouth. Hang on, Andy Capp is a pun on “handicap,” isn’t it? I just got that. I looked it up on Wikipedia for verification, and apparently Andy Capp lives in Hartlepool and even has a statue there in his honour. While I’m not sure commemorating a fictional wife-beating alcoholic is the best thing ever, Hartlepool’s other big claim to fame is that they once hanged a monkey after mistaking it for a French spy so they’ve only got so much material to work with, civic pride-wise.

Where was I? Oh yes, Agent X. So, the inside of the Omega base is a dangerous place, packed with killer monocular robots, people with unicycles instead of legs, killer monocular robots wearing capes and runaway mine carts. Did I mention that the Omega Base is inside a mine? Well, it is. That explains why there’s a sign saying “mine” on the loading screen. I has assumed it was just Agent X making sure everyone knows he owns that supercar.

Speaking of signs, just look at Agent X puffing away underneath a No Smoking sign. What a rebel, what a man of determination, what a man who’s going to end up being scraped off the walls after a methane explosion.

This section all plays out just as you’d think it would. Once again you’re trying to travel far enough to fill up the bar on the right, and you can do so by running, jumping and kicking. Well, in theory. In practise, the only thing you should ever do during this stage is the jumping kick, which you can see above. It might not be the most graceful martial arts move I’ve ever seen – Agent X looks like a Playmobil figure that’s been forced into a sitting position – but by god is it useful. Not only does it defeat all your enemies with a single hit, complete with a very charming “oof!” speech bubble that appears when you land the telling blow, but it’s fast and responsive and it helps with leaping over the mine carts because they’re immune to getting kicked.

Much like the first section, this is a very enjoyable area. The action’s simple but well-crafted, once again the controls are smooth and the almost Beano-esque cartoon graphics are a lot of fun. It also helps that Agent X is fairly generous with both the amount of lives it gives you and its respawns – so many home computer games of the time have that “here’s your three lives, use ‘em all and piss off” vibe to them, but that’s not the case here. I was a little bit worried when I realised that Agent X was going to feature a variety of different play mechanics, because I’ve played a lot of “multi-event” games over the years and they’re rarely much good, leaving you wishing that the developers had decided on one genre and stuck with it. A game with one well-executed concept is infinitely preferable to a game with several half-arsed sections bolted together, you know? Agent X is doing okay for itself so far, though. Can it keep up this level of quality?

No, it cannot. The next stage is a crosshair shooter game, and it’s also the game’s lowest ebb… which is not to say it’s terrible or anything. Your crosshair is responsive enough and it still looks quite nice, but there are three main problems with it: it’s not very interesting, it goes on for ages and it’s much, much more difficult than the rest of the game.

The aim (hur hur) of the game is simple: the mad professor’s machine will randomly fire a projectile at you from one of the eight yellow doorways. You have to move your crosshair over to the “missile” and shoot it down before it hits you. That’s pretty much it, folks. Between the very non-missile-launcher-looking doorways, the bright colours and that fact that all the missiles flying at you are platonic solids, it’s a bit like being attacked by a weaponised Play-Doh Fun Factory.

Once you’ve destroyed enough missiles to fill about seventy-five percent of the objective bar, things start getting extremely hectic. Missiles are constantly spewing from the doorways, and it’s nigh-impossible to move the cursor fast enough to hit them all unless, like me, you stumble onto a secret technique. You see, there’s a very specific height at which you can place your crosshair, a vertical level that allows you to hit both the high and low missiles without having to move the crosshair up or down. Figuring this out was the only way I managed to clear this stage, because obviously only having one axis of movement to worry about makes things, well, fifty percent easier. Speaking of making things easier, if you decide to give Agent X a go for yourself, for the love of god make sure you figure out how to set up a joystick on your Spectrum emulator (or actual Spectrum, I guess). If you don’t, you’ll have to use the keyboard controls. You know, the standard Spectrum keyboard controls, where Q and A move your crosshair up and down while O and P move it left and right, with the bottom row a fire. Trying to play a crosshair shooter with these controls is the digital equivalent of rubbing you stomach and patting your head at the same time, and was surely a huge contributing factor as to why I liked this stage the least.

Oh well, it’s over now. Agent X puts a bullet in the mad professor’s skull while quipping “This one’s for you, pal.” Given Agent X’s attire, it’s almost impossible not to read that line in a Humphrey Bogart voice. I’m not sure what Agent X shot the professor with, but it seems to have set his head on fire so I suppose that means it’s the end of the game?

Of course not, I’ve got to blow up the villain’s underground base! You can’t have a game set in a villain’s underground base and not have it explode at the end, although in Agent X’s case things are a touch more complicated than usual. Normally there’s some huge piece of machinery you can overload or even that classic, the self-destruct button, but that’s not the case here. Instead, Agent X takes to the skies in his helicopter. His goal? To fly out of the base, collect a bomb, fly back into the base, deposit the bomb and then escape the base again. Sure, that sounds like a good use of my time.

So now we’re flying a helicopter. It can move up, down and in one horizontal direction. If you press the other direction, the helicopter actually spins across the screen and ends up facing the other way, which will almost certainly get you killed if you try doing it anywhere other than at the designated turning-around points.

The stage is split into two halves – the first is inside the base, where you have to time your movements to pass through shutters that open and close rhythmically and avoid missiles than can be easily baited into launching while you’re a safe distance away from them. Don’t worry, the helicopter has no momentum, so tricking the missiles into launching is very straightforward.

In the second half of area, you’re attacked by some of the professor’s loyal troops. Extremely loyal, given that even though their leader has been killed they’re still willing to take on an attack helicopter armed with nothing more than pistols and jetpacks that seem to be made from rejected fireworks. This part seems a bit more difficult at first – until you realise that because the helicopter’s nose angles downwards when you’re moving, you can shoot diagonally downwards, destroying the jetpack men before they can even lift off. That’s my top tip for this section, then. I've even come up with a little rhyme as a memory aid: get your nose down and the bad guy goes down.

The bomb is a large, round, traditionally cartoonish, Batman-just-can’t get-rid-of-it bomb, because of course it is. Did you not see the rest of this game’s graphics? At the very outside I suppose it might have been a bundle of dynamite.

Now all that’s left is to fly back into the cave, drop off the bomb and leave. Yeah, I know having to essentially do the same thing three times sounds kinda lame, but each run is short enough that it doesn’t get too wearing, and it’s not as though the helicopter’s a pain in the arse to fly or anything.

The game ends with a shocking twist: the professor isn’t dead at all! All you managed to destroy was a “robot simulacrum.” And, you know, his headquarters and all his henchmen. The professor goes on to call Agent X the “son of a silly person,” so we’ve got our sequel hook right there. Agent X is out for revenge in Agent X 2: My Mother Was a God Damn Saint.

The actually is an Agent X 2, and after playing through this game I’m looking forward to giving it a shot one day. Agent X might be a simple game, but it’s well executed and when it goes to Spectrum games I’ll take “well-executed simplicity” any day of the week. The crosshair section is be the weakest part but even that’s not bad, and the rest of the game is a fun little romp blessed by both an engagingly goofy cartoon style and a lack of vicious difficulty spikes. Also, did I mention the lives counter? Because I really do love that thing. All in all, Agent X is easily one of the better ZX Spectrum games I’ve played recently, even with the awful keyboard controls. All that remains is for me to apologise to the residents of Hartlepool, and I’ll see you next time.

29/06/2017

27/06/2017

PAC-MAN CLONE COVERS

Good old Pac-Man, eh? Where would videogames be without the little yellow lump? The first mascot character in games, a true icon of the medium and let’s not forget all those budding programmers who got their start by developing knock-off Pac-Man clones. Yes, there are hundreds of the bloody things – dot-munching, monster-swerving maze chases in a vast panoply of themes and settings across every gaming system of the eighties, but especially on the home computers of the time. So, what I’d thought I’d do is take a look at some cover art from these Pac-Man, ahem, inspired games. Frankly, it’s lucky I enjoy cartoon ghosts so much.

When it comes to these Pac-Man covers, there seems to be three main categories: covers that straight-up say “hey, this is Pac-Man,” covers that take the hungry-orb-versus-angry-ghosts angle and twist it a little, and covers that slap on an entirely new theme like “jungle” or “fish.” Snapper falls into the first category. That’s definitely a screenshot of Pac-Man, even if it’s called Snapper and it’s a slightly different game now. In fact, I had to go and check whether that’s exactly the same maze layout as the original arcade Pac-Man. It isn’t, but the differences are so slight it might as well be. Consider this a baseline, then, but don’t worry – they’re going to get a lot weirder than this.

Ghost Chaser provides a good example of the second type of cover. A vaguely spherical creature composed of a) a mouth and b) insatiable hunger chases down a creature that could well be a ghost. A slimy, gloopy ghost, certainly, maybe the lingering spirit of a wad of chewed gum, but at least partly ectoplasmic. Then you look closer and realise that this Pac-Man wannabe has a tough, gritty edge – he’s packing a pair of six-shooters! And Sega thought they were being so original when they released Shadow the Hedgehog. They may be oddly-shaped, as though someone described the concept of a revolver to a blind person who then tried to shape one out of modelling clay, but they’re definitely supposed to be guns. Which is stupid, what’s the ghost chaser going to do, shoot the ghost? C’mon, man. On the plus side, the guns do mean I can’t help but imagine the ghost chaser has Revolver Ocelot’s voice. “Six Power Pellets. More than enough to kill any ghost that moves!”

Then there’s the third kind of cover, with no ghosts or Pac-Men to be seen. Instead we’re treated to the comic-book stylings of Mazeman! That’s right, Mazeman. By day he’s wealthy millionaire playboy Theseus Mazeington, but when night falls he leaps into action as the mighty Mazeman, guiding the innocent out of hedge mazes in the grounds of stately homes and helping little kids solve the puzzles on their fast-food-restaurant activity sheets. He’s buff, he’s blonde, he provides a good example of why so few superheroes wear red-and-orange costumes – because they tend to look like walking piles of chicken nuggets and ketchup, that’s why. I’ve never played Mazeman and I don’t intend to, but if Mazeman doesn’t have a kid sidekick called Labyrinth Lad I shall be very disappointed.

Speaking of superheroes, here’s the Batman villain Killer Croc, wading through his swampy home while he breaks in his new crocodile-man-sized jeans. Thanks for hiding your reptilian shame, Killer Croc. Of course, the real highlight of this cover is the discordant contrast between a hulking lizardman who uses human skulls as a kicky fashion accessory and the Bubble Bus Software logo. Beep beep, all aboard the Bubble Bus! It’s travelling along the Mini Bus line, stopping at Candy Town, Camp Giggles and Cannibal Monster Bayou!

Gulpman’s cover is a great example of just how much imagination you had to use when playing these old home computer games – the game itself is composed entirely of solid lines and slow-moving ASCII characters, but the cover transports us to an exciting world of lasers, mysterious energy-ghosts and futuristic onesies. Apparently, developers thinking to themselves “you know what Pac-Man was missing? Guns.” was a thing during the eighties.

One thing that does fascinate me about these Pac-Man covers is the many and varied ways the developers chose to draw the “dots” that fill the mazes. In Gulpman’s case, they’ve been rendered as translucent yellow rectangles that are just lying on the floor where any passing Gulpman could trip over them. That’s a compensation lawsuit waiting to happen, that is.

Here’s a, erm, different iteration of Gulpman. Rather than an exciting space adventure with laser battles, this version of Gulpman is all about humanity’s efforts to build the most punchable robot imaginable. They seem to have succeeded in their mission. It’s half Jimmy Olsen, half Gabbo from The Simpsons and all deeply unpleasant to look at. It’s got a propeller beanie, for pity’s sake. My theory is that Robo-Gulpman was designed as a training droid for the bullies of the far future to practice on. The fire blazing in his eyes represents his hatred for his creators, you see.

I really like this cover, it’s got a kind of “sixties kid’s book” vibe to it and that shark-demon-thing is great. It’s facial expression suggests it hasn’t got a clue why it’s chasing this man down but he can’t stop now, maze-chasing is all he knows. Well, maze-chasing and making finger-guns. Some fruit watches on, but it’s not just any fruit, and the game’s features list them as “magical strawberries” and “high-scoring lemons.” How wonderful.

It’s half Pac-Man, half barracuda with the fish-themed Pakacuda, as drawn by someone with only a tenuous understanding of what an octopus looks like. Yes, octopuses do have beaks but no, not like that. That’s more toucan than cephalopod. Still, nice use of green felt-tips to suggest the ocean waters.

The octopuses are looking a bit better in the sequel Supercuda, but it doesn’t matter – I can’t see anything on this cover beyond the fact that the titular Supercuda has human eyes and eyelashes. Is that to make sure you know it’s a lady fish? That eye is genuinely creeping me out a little. If you look at the eel you can see that the artist had some idea of what a fish’s eye should look like, but they went with the human eye anyway, and as a result the Supercuda can at least get some other work appearing in Maybelline commercials.

Something I learned while looking at these covers is that giving Pac-Man teeth makes him roughly one thousand percent more sinister. The tongue isn’t helping, either. I dunno, maybe I just have trouble thinking of Pac-Man as a biological organism. I prefer him as some kind of rolling garbage-disposal automaton, kinda like Wall-E if Wall-E was perpetually haunted by the spectres of the dead. Of course, if Pac-Man isn’t biological then where did Pac-Man Junior come from?

Ah yes, Gobbleman, the one superhero with a worse power than Mazeman. This is what I mean about mouths - this thing is bloody terrifying, with it’s highly-detailed teeth and lack of eyes. It’s like a xenomorph facehugger managed to impregnate a dodgem, and I hate it. No wonder the pellets appear to be flying into Gobbleman’s mouth as fast as possible, anything to end their suffering faster is gratefully welcomed.

I’m immature enough that the phrase “gobble a ghost” gets a chuckle from me. I’m not proud about that fact, but when I was growing up the word “gobble” meant two things – the sounds a turkey makes and fellatio. I wish it wasn’t so, but c’est la vie. At least this is a nice cover. You definitely know you’re getting a Pac-Man game with this one, although I can’t tell which way the ghosts are supposed to be facing: are they leaning to the right because they’re moving to the right, or are those black indentations supposed to be their mouths? What do you mean, “no one cares?” I care. No, wait, hang on, I don’t care. Next!

Moving away from the home computer games briefly, just to say that if you are releasing a Pac-Man clone – or indeed any videogame – then maybe you shouldn’t give it a name that’s a homonym for a racial slur. Just a thought.

Hey, it’s Horace! The almost-mascot of the ZX Spectrum, star of a series of games that I wrote about a long time ago and a creature who appears to have had every last iota of joy sucked from his being. Is there an emoji for “depression” already? Because if not, hey, I know Horace isn’t doing anything. Well, besides appearing as graffiti around my home town. Whatever your views on the rights and wrongs of graffiti, it always cheered me up to look down near the Porter Brook and see Horace’s grim visage staring back up at me.

From the cosily nostalgic to the downright nauseating now, with Jungle Jim the hideous explorer. Okay, so the tiger’s not too bad and the snake’s okay, but Jim himself is… ugh. His face looks like Graeme Souness had radical surgery to give himself anime eyes, but why does he appear to be covered head-to-toe in a thick layer of vaseline? He’s just so oily, which somehow makes the fact that you can see the stubble of his leg hairs even more disturbing. Combine that with being dangerously close to seeing right up Jim’s shorts leg and this is a cover that doesn’t bear looking at for long. Then again, even if you only glance at it for a moment, the thought of a greased-up Jungle Jim pressing his slimy body against yours while his enormous eyes stare deep into your soul will not soon leave your mind.

This is probably the most infamous cover on this list, and yes, there really was an MSX Pac-Man clone called Oh Shit! It’s so named because when you lose a life, a screeching digitised voice shouts “ohhhh shiiiiiit!” at you, presumably in an attempt to get you to stop playing Oh Shit! as quickly as possible.

As for the cover, well, the actual game is a straight-up Pac-Man clone with minimal graphical changes, so quite why the artwork shows you playing as Winnie the Pooh’s severed head is beyond me. I think the red things are supposed to be the pellets you’re eating? Nope, I’m sorry, this one has me stumped. All I can tell you is that when I saw the thumbnail for this picture a while ago, my brain decided to interpret the vague white shape as a pair of underpants, with the red bits being the legs sticking out of the pants. Maybe I’m just not getting enough sleep or something.

Oh Shit! was also released under the name Shit, the publisher apparently deciding that Oh Shit! is a snappy name but it could be snappier. The lack of punctuation on the word “shit” gives it a really underwhelming quality, don’t you think? “Aww shit, the Satanic force of incomprehensible evil is trying to push its way into our reality again. Honey, fetch me the crucifix, would you?”

Also, as noted over at Hardcore Gaming 101, this artwork is lifted directly from the cover of the horror novel The Howling III. I’m going to guess it’s a much more appropriate image in that context.

But wait, there’s yet another cover for Oh Shit! and somehow it manages to be even worse than the other two! What the hell has happened to this man to make him pull that face? He looks like someone’s just sprayed pure capsaicin up his backside. Or maybe he’s punched the screen of that arcade cabinet out of pure frustration, which would explain his mangled hand. Either way, I’m sure we can all agree that if this chap was a real person you’d see his mugshot below a newspaper headline like “Local Man Attempts Hold-Up With Banana” or “Local Man Steals Quad Bike, Crashes Into Slurry Pit.”

“So long, broom, I’ve rendered you obsolete! You hear me? Obsolete!!”

And now, a section I like to call “Pac-Man Analogue Menaced From Behind by Ghost,” beginning with Cruncher Factory. This Pac-Man’s simple facial features mean he’s not nearly as creepy as some of his contemporaries, but he’s expressive enough to capture a real expression of guilt as he’s caught eating the cruncher factory’s valuable metal ingots. That’s some very half-hearted spooking by the ghost, I must say. And what’s going on with its “hands”? Did it die as a result of a terrible high-fiving accident?

“I’ll get my revenge by staring at Pac-Man’s arse, that’ll teach him to eat my friends.”

In which Fake Pac-Man is harassed by the Ku Klux Klan. The ghosts look as though they’re peer-pressuring Fake Pac-Man into trying ecstasy. Don’t do it, Fake Pac-Man, eat that nutritious banana instead.

Sadly, this game isn’t based on the corn snacks of the same name. I’m honestly shocked there wasn’t an officially licensed game based on the Monster Munch crisps, you know – the closest thing I could find are these handheld LCD Monster Munch games, and my life is a little brighter for knowing that these things exist.

Anyway, this cover posits the interesting concept of a vampire Pac-Man. It might sound daft at first – Pac-Man doesn’t even have a neck for a vampire to bite, for starters – but eating all those ghosts is bound to have some kind of supernatural effect on Pac-Man’s physiology. I’ve seen the episodes of the Ghostbusters cartoon where they enter the containment unit, and I can’t imagine Pac-Man’s stomach is much different.

Oh good god, I could have happily gone my entire life without seeing the unnecessarily detailed soles of a fake Pac-Man’s grubby feet. What is this, Deviantart? The rest of the Pac-Man isn’t any more appealing, with the kind face of face you’d see painted on a carousel vehicle at a carnival run by soul-stealing shapeshifters. The ghost’s pretty good, though, with those gaping, vacant eyes… hang on a minute! Horace, you take that sheet off your head right now and get back to either maze-chasing, skiing or avoiding spiders!

See, if I were making a game called Beetlemania I’d have gone down the route of having you play as one of the Beatles, picking up gold records while being chased by screaming fans. Instead, we’ve got regular old beetles. Okay, sure, the game’s inlay does describe them as giant homicidal beetles, but still.

Now that’s not the cover I expected for a game called Blobbo. You’d think it’d star some jolly, rotund creature, not a robot so abstract it’s difficult to figure out where its head starts, a robot standing in a rain of crystalline fruit, licking the sun and firing its chest-lights into the gloom. Please note this is not a complaint. I’m all for game art that looks like the cover to a cyberpunk novel about an evil AI that takes over fruit machines.

I could go on (and on, and on – there are a lot of Pac-Man clones out there) but I think I’ll finish for today with my favourite cover of the bunch. It might not be the most professional, but it’s deeply charming in its simplicity and its basic execution manages to capture some raw emotion – forever pursued by the ghost of a banana, this fake Pac-Man is at the brink of exhaustion, his tongue lolling from his mouth as his stick legs somehow summon the strength to keep him moving, always moving, always searching for the Power Pellet that will save him. There can be no respite, however, and he knows that he is ultimately doomed to become one of the cursed undead. On that slightly depressing note, I’ll bring this article to a close. God speed, Munch-Man.

Snapper, BBC Micro

When it comes to these Pac-Man covers, there seems to be three main categories: covers that straight-up say “hey, this is Pac-Man,” covers that take the hungry-orb-versus-angry-ghosts angle and twist it a little, and covers that slap on an entirely new theme like “jungle” or “fish.” Snapper falls into the first category. That’s definitely a screenshot of Pac-Man, even if it’s called Snapper and it’s a slightly different game now. In fact, I had to go and check whether that’s exactly the same maze layout as the original arcade Pac-Man. It isn’t, but the differences are so slight it might as well be. Consider this a baseline, then, but don’t worry – they’re going to get a lot weirder than this.

Ghost Chaser, Amiga

Ghost Chaser provides a good example of the second type of cover. A vaguely spherical creature composed of a) a mouth and b) insatiable hunger chases down a creature that could well be a ghost. A slimy, gloopy ghost, certainly, maybe the lingering spirit of a wad of chewed gum, but at least partly ectoplasmic. Then you look closer and realise that this Pac-Man wannabe has a tough, gritty edge – he’s packing a pair of six-shooters! And Sega thought they were being so original when they released Shadow the Hedgehog. They may be oddly-shaped, as though someone described the concept of a revolver to a blind person who then tried to shape one out of modelling clay, but they’re definitely supposed to be guns. Which is stupid, what’s the ghost chaser going to do, shoot the ghost? C’mon, man. On the plus side, the guns do mean I can’t help but imagine the ghost chaser has Revolver Ocelot’s voice. “Six Power Pellets. More than enough to kill any ghost that moves!”

Mazeman, ZX Spectrum

Then there’s the third kind of cover, with no ghosts or Pac-Men to be seen. Instead we’re treated to the comic-book stylings of Mazeman! That’s right, Mazeman. By day he’s wealthy millionaire playboy Theseus Mazeington, but when night falls he leaps into action as the mighty Mazeman, guiding the innocent out of hedge mazes in the grounds of stately homes and helping little kids solve the puzzles on their fast-food-restaurant activity sheets. He’s buff, he’s blonde, he provides a good example of why so few superheroes wear red-and-orange costumes – because they tend to look like walking piles of chicken nuggets and ketchup, that’s why. I’ve never played Mazeman and I don’t intend to, but if Mazeman doesn’t have a kid sidekick called Labyrinth Lad I shall be very disappointed.

Classic Muncher, ZX Spectrum

Speaking of superheroes, here’s the Batman villain Killer Croc, wading through his swampy home while he breaks in his new crocodile-man-sized jeans. Thanks for hiding your reptilian shame, Killer Croc. Of course, the real highlight of this cover is the discordant contrast between a hulking lizardman who uses human skulls as a kicky fashion accessory and the Bubble Bus Software logo. Beep beep, all aboard the Bubble Bus! It’s travelling along the Mini Bus line, stopping at Candy Town, Camp Giggles and Cannibal Monster Bayou!

Gulpman, ZX Spectrum

Gulpman’s cover is a great example of just how much imagination you had to use when playing these old home computer games – the game itself is composed entirely of solid lines and slow-moving ASCII characters, but the cover transports us to an exciting world of lasers, mysterious energy-ghosts and futuristic onesies. Apparently, developers thinking to themselves “you know what Pac-Man was missing? Guns.” was a thing during the eighties.

One thing that does fascinate me about these Pac-Man covers is the many and varied ways the developers chose to draw the “dots” that fill the mazes. In Gulpman’s case, they’ve been rendered as translucent yellow rectangles that are just lying on the floor where any passing Gulpman could trip over them. That’s a compensation lawsuit waiting to happen, that is.

Gulpman, Timex Spectrum

Here’s a, erm, different iteration of Gulpman. Rather than an exciting space adventure with laser battles, this version of Gulpman is all about humanity’s efforts to build the most punchable robot imaginable. They seem to have succeeded in their mission. It’s half Jimmy Olsen, half Gabbo from The Simpsons and all deeply unpleasant to look at. It’s got a propeller beanie, for pity’s sake. My theory is that Robo-Gulpman was designed as a training droid for the bullies of the far future to practice on. The fire blazing in his eyes represents his hatred for his creators, you see.

Maze Chase, ZX Spectrum

I really like this cover, it’s got a kind of “sixties kid’s book” vibe to it and that shark-demon-thing is great. It’s facial expression suggests it hasn’t got a clue why it’s chasing this man down but he can’t stop now, maze-chasing is all he knows. Well, maze-chasing and making finger-guns. Some fruit watches on, but it’s not just any fruit, and the game’s features list them as “magical strawberries” and “high-scoring lemons.” How wonderful.

Pakacuda, Commodore 64

It’s half Pac-Man, half barracuda with the fish-themed Pakacuda, as drawn by someone with only a tenuous understanding of what an octopus looks like. Yes, octopuses do have beaks but no, not like that. That’s more toucan than cephalopod. Still, nice use of green felt-tips to suggest the ocean waters.

Supercuda, Commodore 64

The octopuses are looking a bit better in the sequel Supercuda, but it doesn’t matter – I can’t see anything on this cover beyond the fact that the titular Supercuda has human eyes and eyelashes. Is that to make sure you know it’s a lady fish? That eye is genuinely creeping me out a little. If you look at the eel you can see that the artist had some idea of what a fish’s eye should look like, but they went with the human eye anyway, and as a result the Supercuda can at least get some other work appearing in Maybelline commercials.

Oricmunch, Oric

Something I learned while looking at these covers is that giving Pac-Man teeth makes him roughly one thousand percent more sinister. The tongue isn’t helping, either. I dunno, maybe I just have trouble thinking of Pac-Man as a biological organism. I prefer him as some kind of rolling garbage-disposal automaton, kinda like Wall-E if Wall-E was perpetually haunted by the spectres of the dead. Of course, if Pac-Man isn’t biological then where did Pac-Man Junior come from?

Gobbleman, ZX Spectrum

Ah yes, Gobbleman, the one superhero with a worse power than Mazeman. This is what I mean about mouths - this thing is bloody terrifying, with it’s highly-detailed teeth and lack of eyes. It’s like a xenomorph facehugger managed to impregnate a dodgem, and I hate it. No wonder the pellets appear to be flying into Gobbleman’s mouth as fast as possible, anything to end their suffering faster is gratefully welcomed.

Gobble A Ghost, ZX Spectrum

I’m immature enough that the phrase “gobble a ghost” gets a chuckle from me. I’m not proud about that fact, but when I was growing up the word “gobble” meant two things – the sounds a turkey makes and fellatio. I wish it wasn’t so, but c’est la vie. At least this is a nice cover. You definitely know you’re getting a Pac-Man game with this one, although I can’t tell which way the ghosts are supposed to be facing: are they leaning to the right because they’re moving to the right, or are those black indentations supposed to be their mouths? What do you mean, “no one cares?” I care. No, wait, hang on, I don’t care. Next!

Paccie, Playstation 2

Moving away from the home computer games briefly, just to say that if you are releasing a Pac-Man clone – or indeed any videogame – then maybe you shouldn’t give it a name that’s a homonym for a racial slur. Just a thought.

Hungry Horace, ZX Spectrum

Hey, it’s Horace! The almost-mascot of the ZX Spectrum, star of a series of games that I wrote about a long time ago and a creature who appears to have had every last iota of joy sucked from his being. Is there an emoji for “depression” already? Because if not, hey, I know Horace isn’t doing anything. Well, besides appearing as graffiti around my home town. Whatever your views on the rights and wrongs of graffiti, it always cheered me up to look down near the Porter Brook and see Horace’s grim visage staring back up at me.

Jungle Jim, Amiga

From the cosily nostalgic to the downright nauseating now, with Jungle Jim the hideous explorer. Okay, so the tiger’s not too bad and the snake’s okay, but Jim himself is… ugh. His face looks like Graeme Souness had radical surgery to give himself anime eyes, but why does he appear to be covered head-to-toe in a thick layer of vaseline? He’s just so oily, which somehow makes the fact that you can see the stubble of his leg hairs even more disturbing. Combine that with being dangerously close to seeing right up Jim’s shorts leg and this is a cover that doesn’t bear looking at for long. Then again, even if you only glance at it for a moment, the thought of a greased-up Jungle Jim pressing his slimy body against yours while his enormous eyes stare deep into your soul will not soon leave your mind.

Oh Shit!, MSX

This is probably the most infamous cover on this list, and yes, there really was an MSX Pac-Man clone called Oh Shit! It’s so named because when you lose a life, a screeching digitised voice shouts “ohhhh shiiiiiit!” at you, presumably in an attempt to get you to stop playing Oh Shit! as quickly as possible.

As for the cover, well, the actual game is a straight-up Pac-Man clone with minimal graphical changes, so quite why the artwork shows you playing as Winnie the Pooh’s severed head is beyond me. I think the red things are supposed to be the pellets you’re eating? Nope, I’m sorry, this one has me stumped. All I can tell you is that when I saw the thumbnail for this picture a while ago, my brain decided to interpret the vague white shape as a pair of underpants, with the red bits being the legs sticking out of the pants. Maybe I’m just not getting enough sleep or something.

Shit, MSX

Oh Shit! was also released under the name Shit, the publisher apparently deciding that Oh Shit! is a snappy name but it could be snappier. The lack of punctuation on the word “shit” gives it a really underwhelming quality, don’t you think? “Aww shit, the Satanic force of incomprehensible evil is trying to push its way into our reality again. Honey, fetch me the crucifix, would you?”

Also, as noted over at Hardcore Gaming 101, this artwork is lifted directly from the cover of the horror novel The Howling III. I’m going to guess it’s a much more appropriate image in that context.

Oh Shit!, MSX

But wait, there’s yet another cover for Oh Shit! and somehow it manages to be even worse than the other two! What the hell has happened to this man to make him pull that face? He looks like someone’s just sprayed pure capsaicin up his backside. Or maybe he’s punched the screen of that arcade cabinet out of pure frustration, which would explain his mangled hand. Either way, I’m sure we can all agree that if this chap was a real person you’d see his mugshot below a newspaper headline like “Local Man Attempts Hold-Up With Banana” or “Local Man Steals Quad Bike, Crashes Into Slurry Pit.”

Vacuumania, MSX

“So long, broom, I’ve rendered you obsolete! You hear me? Obsolete!!”

Cruncher Factory, Amiga

And now, a section I like to call “Pac-Man Analogue Menaced From Behind by Ghost,” beginning with Cruncher Factory. This Pac-Man’s simple facial features mean he’s not nearly as creepy as some of his contemporaries, but he’s expressive enough to capture a real expression of guilt as he’s caught eating the cruncher factory’s valuable metal ingots. That’s some very half-hearted spooking by the ghost, I must say. And what’s going on with its “hands”? Did it die as a result of a terrible high-fiving accident?

Ghost’s Revenge, ZX Spectrum

“I’ll get my revenge by staring at Pac-Man’s arse, that’ll teach him to eat my friends.”

Munch Man 64, Commodore 64

In which Fake Pac-Man is harassed by the Ku Klux Klan. The ghosts look as though they’re peer-pressuring Fake Pac-Man into trying ecstasy. Don’t do it, Fake Pac-Man, eat that nutritious banana instead.

Monster Munch, Commodore 64

Sadly, this game isn’t based on the corn snacks of the same name. I’m honestly shocked there wasn’t an officially licensed game based on the Monster Munch crisps, you know – the closest thing I could find are these handheld LCD Monster Munch games, and my life is a little brighter for knowing that these things exist.

Anyway, this cover posits the interesting concept of a vampire Pac-Man. It might sound daft at first – Pac-Man doesn’t even have a neck for a vampire to bite, for starters – but eating all those ghosts is bound to have some kind of supernatural effect on Pac-Man’s physiology. I’ve seen the episodes of the Ghostbusters cartoon where they enter the containment unit, and I can’t imagine Pac-Man’s stomach is much different.

Sprite Man, Commodore 64

Oh good god, I could have happily gone my entire life without seeing the unnecessarily detailed soles of a fake Pac-Man’s grubby feet. What is this, Deviantart? The rest of the Pac-Man isn’t any more appealing, with the kind face of face you’d see painted on a carousel vehicle at a carnival run by soul-stealing shapeshifters. The ghost’s pretty good, though, with those gaping, vacant eyes… hang on a minute! Horace, you take that sheet off your head right now and get back to either maze-chasing, skiing or avoiding spiders!

Beetlemania, ZX Spectrum

See, if I were making a game called Beetlemania I’d have gone down the route of having you play as one of the Beatles, picking up gold records while being chased by screaming fans. Instead, we’ve got regular old beetles. Okay, sure, the game’s inlay does describe them as giant homicidal beetles, but still.

Blobbo, ZX Spectrum

Now that’s not the cover I expected for a game called Blobbo. You’d think it’d star some jolly, rotund creature, not a robot so abstract it’s difficult to figure out where its head starts, a robot standing in a rain of crystalline fruit, licking the sun and firing its chest-lights into the gloom. Please note this is not a complaint. I’m all for game art that looks like the cover to a cyberpunk novel about an evil AI that takes over fruit machines.

Munch-Man, ZX Spectrum

I could go on (and on, and on – there are a lot of Pac-Man clones out there) but I think I’ll finish for today with my favourite cover of the bunch. It might not be the most professional, but it’s deeply charming in its simplicity and its basic execution manages to capture some raw emotion – forever pursued by the ghost of a banana, this fake Pac-Man is at the brink of exhaustion, his tongue lolling from his mouth as his stick legs somehow summon the strength to keep him moving, always moving, always searching for the Power Pellet that will save him. There can be no respite, however, and he knows that he is ultimately doomed to become one of the cursed undead. On that slightly depressing note, I’ll bring this article to a close. God speed, Munch-Man.

Labels:

cover art,

home computers,

pac-man

23/06/2017

ENDURO RACER (ARCADE)

I hadn’t actually intended on writing about today’s game, but the other day I had twenty minutes to while away so I turned to Sega’s super-scaler arcade games of the mid eighties. A pretty decent shout as a time-passer, I’m sure you’ll agree, and the game in question was the 1986 dirt-bike-em-up Enduro Racer. And, hey, I’ve played it now, so I might as well write an article about it. You know, after I’d gone back to it a bit later and put some practise in because it’s very unlikely I’d reach the end of any Sega arcade racer with only twenty minutes of practice.

Here is a dirt bike now, taking pride of place on the title screen. Having said that, motorcycle aficionados would probably tell me that “dirt bike” refers to a specific kind of off-road bike and the one pictured here doesn’t fall into that category, thus exposing my lack of motorcycle knowledge for all the world to see. I’m not worried about that, though. Not knowing what I’m talking about has never stopped me writing these articles before.

Also on the title screen is the titular racer themselves, currently attempting to bunny-hop over the game’s logo. What a great logo it is too, check out that colour palette. I believe it’s what the kids these days would call “aesthetic,” but which I would describe as “kinda like the logo from the old Visionaries toy line.” Oh, and “enduro” is a kind of mostly off-road motorcycle race. Well, I think that’s the title screen covered, I should probably play the actual game.

Vroom vroom, beep beep – in the biggest shock at VGJunk since Barbie and the Magic of Pegasus wasn’t terrible, it turns out that a game called Enduro Racer is a racing game. An against-the-clock checkpoint racer, to be precise, so very much in line with Sega’s other super-scaler racing games like OutRun and Hang-On. There are other motorcyclists on the track, but they’re just there to get in the way and to stop our racer from feeling too lonely: the goal is simply to pass each checkpoint before you run out of time.

When Enduro Racer came out, Sega had already released a much-loved arcade motorbike racing game in the form of the previously-mentioned Hang-On. So, what does Enduro Racer do differently to Hang-On? Well, for one thing you can perform wheelies. Pull back on the handlebars to pop a wheelie, as seen above. It has no practical use when you’re racing on flat ground, but then if practicality is at the forefront of your mind when pulling a wheelie then you’re doing it wrong.

The other thing Enduro Racer has is jumps. In fact, jumps are the games most prominent mechanic besides "driving fast" and the most frequent cause of crashes and accidents. You can see one coming up, it’s the ridge of dirt on the track’s horizon. When you hit it, your bike will fly into the air, but you have two options when it comes to getting airborne.

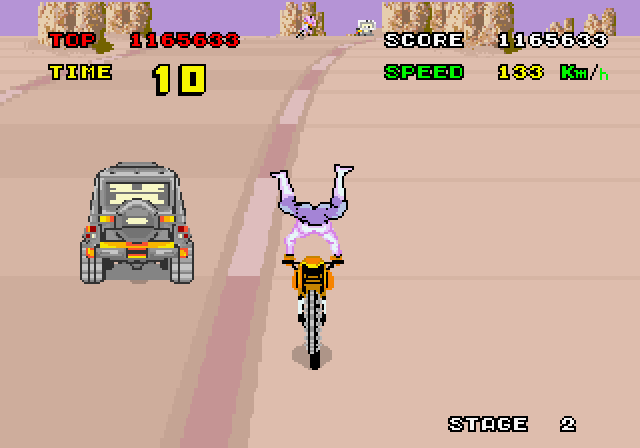

Option one is to drive straight into them. You’ll hop a reasonable height into the air, but this comes with downsides. The first is that if you don’t pull back on the handlebars to correct your flight, your racer will land heavily on their front wheel and fall arse-over-tit, coming off their bike, flopping at the side of the road and experiencing an unpleasant mix of pain, embarrassment and terror at the huge bike repair bills they’ve just accrued. The other downside is that, as you can see above, when they’re in the air your racer positions themselves in an extremely unflattering pose seemingly based on a splay-legged frog and designed to force the viewer to ponder the rider’s perineum.

The roadside signs promising delicious, refreshing beer serve only to further mock the rider as they lay sprawled on the ground. I have to say, the player character of Enduro Racer does come across as a very ungainly sort, their limbs flailing in the breeze as they make barely-controlled jumps, their mangled body tossed around by each crash and collision in the manner of a ragdoll filled with wet tissue. And here I thought the entire point of riding a motorbike was to look cool.

Alternatively, if you’re pulling a wheelie when you hit a jump, you jump. You launch, you soar, you become a goddamn one-man space program. You also give up any control over your bike for a long period of time, which makes landing tricky, to put it mildly. If you perform one of these huge jumps on a ramp just before a corner, tough luck. You’re going to fly off the side of the course and probably straight into something solid, because you can’t steer in mid-air. However, you can jump over a lot of obstacles this way, which is useful because Enduro Racer’s designers were very fond of placing sections packed with smaller obstacles such as rocks just after a jump. That means you’ve got two choices: do a short jump for greater aerial control but then you have to slalom though the obstacles, or risk the big jump, go right over all the obstacles and pray you don’t land in a roadside tree.

Jumping aside, Enduro Racer is very much what you’d expect from a Sega arcade racer of the time. It’s fast, the super-scaler sprite manipulation gives a great feeling of depth and while the handling on your bike is perhaps not quite as tight as it is in some of Enduro Racer's fellow arcade driving games, it’s still good and there’s a lot of fun to be had as you weave your way through the other riders and see your rider kick their leg out for balance as you scream around a tight corner.

After the gentle green countryside of the first zone, passing through the checkpoint takes our racer into a dusty desert scene of parched earth, boulders and hollow, dead trees that are still just as sturdy as their healthier counterparts in the last scene and will make your bike explode if you ride into them at two hundred kilometres an hour.

Disappointingly, there’s only one route through Enduro Racer, with neither the branching paths found in OutRun nor the different courses of Hang-On. This rather limits the replayability of the game, but what is there looks nice, at least.

Okay, “looks nice” might not be the perfect phrasing when we’re looking at the extreme wedgie suffered by the rider. He’s going to need a motorised winch to drag his leathers out of his arsecrack once this race is over, the poor bastard.

As well as other bikers, there are also jeeps patrolling the course and generally getting in your way. I’m not sure whether they’re supposed to be part of the same race as you or not. They’re definitely driving fast enough to suggest they're part of a race, so maybe there was a mix-up with the local 4X4 racer’s group and the track was double-booked.

Stage three is a watery landscape of bushes and ancient ruins. And, you know, water. It’s also where Enduro Racer’s difficulty starts to pick up, and make no mistake – beating the timer and reaching the final goal is no easy task, even when you fiddle with the game’s dipswitches and lower the difficulty level. Time limits are extremely tight, and collisions – which Enduro Racer seems much more keen about foisting on you than in other Sega racers – eat up a lot of precious seconds. This shouldn’t be too surprising, though. All of Sega’s other super-scaler racers are bloody hard, too. I think it’s fair to say I’ve played a lot of OutRun and I’m nowhere near able to consistently reach the goal on the default difficulty.

It doesn’t help that there’s no clear definition about which bits of the water you can ride on. You can get away with going off the course a little bit, but stray too far out and you’ll sink to the briny depths, ruing the decision to hold a motorcycle race on The Fens.

There are also a few sections where you have to use the wheelie-powered mega jump to clear long stretches of water, and if you don’t make the jump then you’ll slowly trundle through the shallow water as the other bikers sail over your head.

Enduro Racer’s relationship with its own jumping mechanics is a strange one. For one thing, they turn large segments of the game into almost a memory test – can you remember which jumps have enough straight road beyond them to make a big jump worthwhile and which ones have a curve viciously placed straight afterwards that will make you crash if you don’t use the small jump? Sometimes you can make a decision based on the track you can see coming up, but because Enduro Racer’s courses are full of hills and dips it’s not always possible to see what’s coming up. Then there’s the issue of fun. You’re including the ability to perform ridiculously huge jumps in your racing game, but then asking me not to make ridiculous jumps every time the opportunity presents itself? C’mon, man, that’s not right. If there’s one thing I don’t associate with Sega’s eighties arcade games, it’s the concept of restraint.

The next stage goes back to the desert, but there’s a twist: your bike skids a lot more when turning corners, presumably because you’re racing on loose sand. Hey, I didn’t say it was an exciting twist. Okay, that’s a bit unfair, I did actually enjoy the lowered traction in this stage, it mixed up the gameplay a bit in a way that felt appropriate.

Is there anything else to add about this stage? Erm, no, not really. You race, you slide around, you consider a new career as a crash test dummy because at least that way some useful scientific data might come out of you embedding your ribcage into a tree trunk.

Lastly we’re at the beach, that classic staple of Sega’s racing games. The sea is blue, the sand is white, the palm trees sway in the breeze and it all looks rather nice. Enduro Racer is a nice-looking game, especially in motion, and when you combine that with the possibility of playing it on an arcade cabinet shaped like an actual motorbike and mix in a catchy musical theme by OutRun composer Hiroshi Kawaguchi, it’s easy to overlook Enduro Racer’s gameplay failings and enjoy it as a spectacle.

I don’t think this spectator is going to being enjoying the spectacle in about half a second, when I wedge my front tyre right up against his uvula. I was trying to avoid the jeeps, you see, and I may have gone a little off-piste.

There’s the finish line, and happily there’s a jump right before the goal so you can hit it and leap right over the entire thing, clearing the advertising hoardings completely and ending the game as I played most of it: in mid-air.

Rather than ending the game with some special artwork or a brief animation in the vein of OutRun’s endings, Enduro Racer takes a different tack and goes with a heartfelt speech that boils down to “it’s not the winning, it’s the taking part.” Here it is in full:

“Enduro” is a symbolic journey through life via the media of a race. The results are insignificant and what really counts is competing. Of particular importance are the lessons to be learned concerning one’s self from the various encounters you experience along the way. There is no victor or loser in this test of endurance. The only thing that really matters is that you make a commitment to begin the long and trying trek. This game is dedicated to all of the “life riders” who have started out on the solitary trip to find their own individual limits.

Last but not least may we sincerely congratulate you on a perfect run.

I’m surprised it didn’t end with “love and kisses, Sega,” frankly. Maybe it’s just because I’m getting soppier in my old age, but I genuinely found this message heartwarming, because it’s true – who gives a shit whether you’re “good” at videogames? Play ‘em, have fun, find your own individual limits. I found my own individual limit for Enduro Racer, that’s for sure – about half-an-hour’s play at a time, on the lowest difficulty setting.

So, Enduro Racer isn’t quite an enduring classic. It’s a good game, a solid game, a game with issues but one that still provides high-speed racing action in Sega’s trademark vibrant style… but it can’t quite keep up with its contemporaries. Part of that is that familiarity breeds contempt, and if you’ve already played Hang-On then you’ll probably feel that Enduro Racer is more of the same but with the occasionally frustrating jumping mechanics bolted on. Beyond that, though, Enduro Racer is just lacking that certain spark that so many other Sega super-scaler games possessed. It doesn’t have the intensity of Afterburner, the bonkers-ness of Space Harrier or the sheer cool of OutRun – but if that’s the level of game you’re falling just short of, then you’re not doing bad. Speaking of OutRun, according to Wikipedia (so take it with a pinch of salt) both OutRun and Enduro Racer were released on the same day, and if that’s the case and they were being developed concurrently then I can imagine OutRun being prioritised over Enduro Racer.

To return to the beginning of the article: when I was looking for a fun, simple game to fill twenty minutes and decided on Enduro Racer, did I make a good choice? I think I did. It’s not the greatest, but then it didn’t have to be. Did you learn nothing from that ending text?

Here is a dirt bike now, taking pride of place on the title screen. Having said that, motorcycle aficionados would probably tell me that “dirt bike” refers to a specific kind of off-road bike and the one pictured here doesn’t fall into that category, thus exposing my lack of motorcycle knowledge for all the world to see. I’m not worried about that, though. Not knowing what I’m talking about has never stopped me writing these articles before.

Also on the title screen is the titular racer themselves, currently attempting to bunny-hop over the game’s logo. What a great logo it is too, check out that colour palette. I believe it’s what the kids these days would call “aesthetic,” but which I would describe as “kinda like the logo from the old Visionaries toy line.” Oh, and “enduro” is a kind of mostly off-road motorcycle race. Well, I think that’s the title screen covered, I should probably play the actual game.

Vroom vroom, beep beep – in the biggest shock at VGJunk since Barbie and the Magic of Pegasus wasn’t terrible, it turns out that a game called Enduro Racer is a racing game. An against-the-clock checkpoint racer, to be precise, so very much in line with Sega’s other super-scaler racing games like OutRun and Hang-On. There are other motorcyclists on the track, but they’re just there to get in the way and to stop our racer from feeling too lonely: the goal is simply to pass each checkpoint before you run out of time.

When Enduro Racer came out, Sega had already released a much-loved arcade motorbike racing game in the form of the previously-mentioned Hang-On. So, what does Enduro Racer do differently to Hang-On? Well, for one thing you can perform wheelies. Pull back on the handlebars to pop a wheelie, as seen above. It has no practical use when you’re racing on flat ground, but then if practicality is at the forefront of your mind when pulling a wheelie then you’re doing it wrong.

The other thing Enduro Racer has is jumps. In fact, jumps are the games most prominent mechanic besides "driving fast" and the most frequent cause of crashes and accidents. You can see one coming up, it’s the ridge of dirt on the track’s horizon. When you hit it, your bike will fly into the air, but you have two options when it comes to getting airborne.

Option one is to drive straight into them. You’ll hop a reasonable height into the air, but this comes with downsides. The first is that if you don’t pull back on the handlebars to correct your flight, your racer will land heavily on their front wheel and fall arse-over-tit, coming off their bike, flopping at the side of the road and experiencing an unpleasant mix of pain, embarrassment and terror at the huge bike repair bills they’ve just accrued. The other downside is that, as you can see above, when they’re in the air your racer positions themselves in an extremely unflattering pose seemingly based on a splay-legged frog and designed to force the viewer to ponder the rider’s perineum.

The roadside signs promising delicious, refreshing beer serve only to further mock the rider as they lay sprawled on the ground. I have to say, the player character of Enduro Racer does come across as a very ungainly sort, their limbs flailing in the breeze as they make barely-controlled jumps, their mangled body tossed around by each crash and collision in the manner of a ragdoll filled with wet tissue. And here I thought the entire point of riding a motorbike was to look cool.

Alternatively, if you’re pulling a wheelie when you hit a jump, you jump. You launch, you soar, you become a goddamn one-man space program. You also give up any control over your bike for a long period of time, which makes landing tricky, to put it mildly. If you perform one of these huge jumps on a ramp just before a corner, tough luck. You’re going to fly off the side of the course and probably straight into something solid, because you can’t steer in mid-air. However, you can jump over a lot of obstacles this way, which is useful because Enduro Racer’s designers were very fond of placing sections packed with smaller obstacles such as rocks just after a jump. That means you’ve got two choices: do a short jump for greater aerial control but then you have to slalom though the obstacles, or risk the big jump, go right over all the obstacles and pray you don’t land in a roadside tree.

Jumping aside, Enduro Racer is very much what you’d expect from a Sega arcade racer of the time. It’s fast, the super-scaler sprite manipulation gives a great feeling of depth and while the handling on your bike is perhaps not quite as tight as it is in some of Enduro Racer's fellow arcade driving games, it’s still good and there’s a lot of fun to be had as you weave your way through the other riders and see your rider kick their leg out for balance as you scream around a tight corner.

After the gentle green countryside of the first zone, passing through the checkpoint takes our racer into a dusty desert scene of parched earth, boulders and hollow, dead trees that are still just as sturdy as their healthier counterparts in the last scene and will make your bike explode if you ride into them at two hundred kilometres an hour.

Disappointingly, there’s only one route through Enduro Racer, with neither the branching paths found in OutRun nor the different courses of Hang-On. This rather limits the replayability of the game, but what is there looks nice, at least.

Okay, “looks nice” might not be the perfect phrasing when we’re looking at the extreme wedgie suffered by the rider. He’s going to need a motorised winch to drag his leathers out of his arsecrack once this race is over, the poor bastard.

As well as other bikers, there are also jeeps patrolling the course and generally getting in your way. I’m not sure whether they’re supposed to be part of the same race as you or not. They’re definitely driving fast enough to suggest they're part of a race, so maybe there was a mix-up with the local 4X4 racer’s group and the track was double-booked.

Stage three is a watery landscape of bushes and ancient ruins. And, you know, water. It’s also where Enduro Racer’s difficulty starts to pick up, and make no mistake – beating the timer and reaching the final goal is no easy task, even when you fiddle with the game’s dipswitches and lower the difficulty level. Time limits are extremely tight, and collisions – which Enduro Racer seems much more keen about foisting on you than in other Sega racers – eat up a lot of precious seconds. This shouldn’t be too surprising, though. All of Sega’s other super-scaler racers are bloody hard, too. I think it’s fair to say I’ve played a lot of OutRun and I’m nowhere near able to consistently reach the goal on the default difficulty.

It doesn’t help that there’s no clear definition about which bits of the water you can ride on. You can get away with going off the course a little bit, but stray too far out and you’ll sink to the briny depths, ruing the decision to hold a motorcycle race on The Fens.

There are also a few sections where you have to use the wheelie-powered mega jump to clear long stretches of water, and if you don’t make the jump then you’ll slowly trundle through the shallow water as the other bikers sail over your head.

Enduro Racer’s relationship with its own jumping mechanics is a strange one. For one thing, they turn large segments of the game into almost a memory test – can you remember which jumps have enough straight road beyond them to make a big jump worthwhile and which ones have a curve viciously placed straight afterwards that will make you crash if you don’t use the small jump? Sometimes you can make a decision based on the track you can see coming up, but because Enduro Racer’s courses are full of hills and dips it’s not always possible to see what’s coming up. Then there’s the issue of fun. You’re including the ability to perform ridiculously huge jumps in your racing game, but then asking me not to make ridiculous jumps every time the opportunity presents itself? C’mon, man, that’s not right. If there’s one thing I don’t associate with Sega’s eighties arcade games, it’s the concept of restraint.

The next stage goes back to the desert, but there’s a twist: your bike skids a lot more when turning corners, presumably because you’re racing on loose sand. Hey, I didn’t say it was an exciting twist. Okay, that’s a bit unfair, I did actually enjoy the lowered traction in this stage, it mixed up the gameplay a bit in a way that felt appropriate.

Is there anything else to add about this stage? Erm, no, not really. You race, you slide around, you consider a new career as a crash test dummy because at least that way some useful scientific data might come out of you embedding your ribcage into a tree trunk.

Lastly we’re at the beach, that classic staple of Sega’s racing games. The sea is blue, the sand is white, the palm trees sway in the breeze and it all looks rather nice. Enduro Racer is a nice-looking game, especially in motion, and when you combine that with the possibility of playing it on an arcade cabinet shaped like an actual motorbike and mix in a catchy musical theme by OutRun composer Hiroshi Kawaguchi, it’s easy to overlook Enduro Racer’s gameplay failings and enjoy it as a spectacle.

I don’t think this spectator is going to being enjoying the spectacle in about half a second, when I wedge my front tyre right up against his uvula. I was trying to avoid the jeeps, you see, and I may have gone a little off-piste.

There’s the finish line, and happily there’s a jump right before the goal so you can hit it and leap right over the entire thing, clearing the advertising hoardings completely and ending the game as I played most of it: in mid-air.

Rather than ending the game with some special artwork or a brief animation in the vein of OutRun’s endings, Enduro Racer takes a different tack and goes with a heartfelt speech that boils down to “it’s not the winning, it’s the taking part.” Here it is in full:

“Enduro” is a symbolic journey through life via the media of a race. The results are insignificant and what really counts is competing. Of particular importance are the lessons to be learned concerning one’s self from the various encounters you experience along the way. There is no victor or loser in this test of endurance. The only thing that really matters is that you make a commitment to begin the long and trying trek. This game is dedicated to all of the “life riders” who have started out on the solitary trip to find their own individual limits.

Last but not least may we sincerely congratulate you on a perfect run.

I’m surprised it didn’t end with “love and kisses, Sega,” frankly. Maybe it’s just because I’m getting soppier in my old age, but I genuinely found this message heartwarming, because it’s true – who gives a shit whether you’re “good” at videogames? Play ‘em, have fun, find your own individual limits. I found my own individual limit for Enduro Racer, that’s for sure – about half-an-hour’s play at a time, on the lowest difficulty setting.

So, Enduro Racer isn’t quite an enduring classic. It’s a good game, a solid game, a game with issues but one that still provides high-speed racing action in Sega’s trademark vibrant style… but it can’t quite keep up with its contemporaries. Part of that is that familiarity breeds contempt, and if you’ve already played Hang-On then you’ll probably feel that Enduro Racer is more of the same but with the occasionally frustrating jumping mechanics bolted on. Beyond that, though, Enduro Racer is just lacking that certain spark that so many other Sega super-scaler games possessed. It doesn’t have the intensity of Afterburner, the bonkers-ness of Space Harrier or the sheer cool of OutRun – but if that’s the level of game you’re falling just short of, then you’re not doing bad. Speaking of OutRun, according to Wikipedia (so take it with a pinch of salt) both OutRun and Enduro Racer were released on the same day, and if that’s the case and they were being developed concurrently then I can imagine OutRun being prioritised over Enduro Racer.

To return to the beginning of the article: when I was looking for a fun, simple game to fill twenty minutes and decided on Enduro Racer, did I make a good choice? I think I did. It’s not the greatest, but then it didn’t have to be. Did you learn nothing from that ending text?

Labels:

Arcade,

enduro racer,

racing,

sega

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)